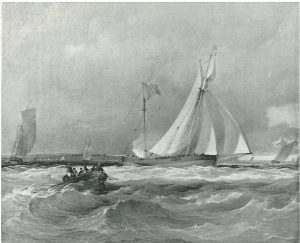

Alarm. Winning the Ladies’ Challenge Cup at Cowes, August 1830.

In preparing the following work, an attempt has been made to trace the progress of British yachting from its earliest stages, and, in doing so, it may be thought that undue prominence has been given to match-sailing. This, however, is inevitable, for to competitive sailing alone is due the advances made from time to time in yacht architecture. It is not without interest to note that progress during some periods was slow, and even non-existent, simply because racing craft had assumed highly objectionable features. All that was good in our racing yachts, of every period, was quickly applied to perfecting vessels for general pleasure purposes, but bad features were frequently mistaken for good; so that, yachts sadly wanting in beam were built for cruising during the time that the racing measurement favoured that type; and it was only after the abolition of ‘tonnage’ measurements that the cruising yacht once more assumed reasonable proportions, absorbing at the same time the good features of the modern racing type. At the present day we have arrived at a point when it may be reasonably expected that no difference will exist, except in size of spars, between the two types of vessel. That was the case in the days when the America won her cup at Cowes; but, for the last thirty-five years, or more, the history of British yachting resolved itself into a struggle between legislators, on the one hand, trying to prevent yacht-racing from producing a bad type of vessel, and designers, on the other, exerting all their ingenuity to find weak spots in the rules set before them.

It may be thought that sufficient space has not been devoted to the various attempts to regain the America Cup. This, however, is a threadbare subject, and, beyond an example of praiseworthy perseverance, there is little to learn from these matches. That Mr. Ashbury was not successful is not surprising; and, in the subsequent challenges, the advantage lay entirely on the side of the defenders. The success of small British yachts, such as Madge, had opened the eyes of American yachtsmen to the value of deep keels as opposed to shallow centre-plate vessels, so, without falling into the error of abandoning the great beam of the national type, they met Genesta, Galatea, and Thistle with yachts in which artificial stability was growing more and more pronounced. Thus, Thistle, our first step in the process of shaking off the tonnage rules, competed with a vessel of a type such as was not seen in our waters until some six years later.

In placing this volume before the public we have to thank the many subscribers who have rendered its production possible, and we trust that it will be found acceptable to that great body of British yachtsmen who see much to admire in the old vessels of former days and in the sturdy men who sailed them.

The Editor

Click here to start reading Chapter 1 or download a pdf of this chapter.