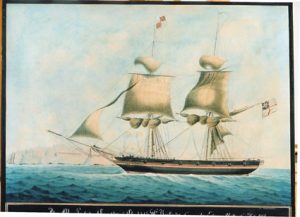

Watercolour with ink and body colour

Watercolour with ink and body colour

44.5cm x 58cm

Signed: N. Cammillieri

Built: Falmouth, 1810

193 34/94 tons

Captain Kirkness received his commission on 4th May 1814, having apparently purchased the Packet from the executors of the late Captain Cocks, RN, the previous commander.

Lloyds List records the voyage on which this portrait was painted. Having arrived at Falmouth from a North Atlantic voyage on 22nd May 1817 the Packet sailed for the Mediterranean on the 10th June. She subsequently arrived at Gibraltar on the 20th June and sailed for Malta on the 24th.

The signal flag shown in the painting is known to identify this Packet between 1810 and 1827. The artist has also shown her flying the white ensign although Packets, as privately owned vessels, were only entitled to fly the red ensign – since 1674 the only legal ensign for British merchant ships. However, this painting is good evidence that, at least on this occasion, her commander chose to fly a white ensign; or, at the very least insisted Cammillieri showed her flying one. Either way it indicates a certain frame of mind.

Captain Kirkness was not alone in adopting this practice. Timothy West (Flags at Sea, London 1986 p34) says that it was occasionally resorted to, particularly during the first half of the nineteenth century. A correspondent in The Mariner’s Mirror (MM 9 1923 p256) mentions pictures in the Illustrated Times of 1856 showing the Schomberg and the Donald Mackay, both merchant and both flying the white ensign. He asked whether it was customary for mail ships to wear the white ensign at that period? Mr. C. King, on giving the annual lecture at Goldsmith’s Hall in 1936 on the subject of Marine Art, had no answer. He could only refer to the ‘flag puzzles which occasionally appear in marine art’, asking again, ‘why do white ensigns sometimes appear in merchant ship paintings of the clipper days?’ (MM 22 1936 pp133-160). This portrait of the Countess of Chichester pushes the practice back to at least 1817 and establishes a link with vessels carrying mails. The answer to the question seems to owe more to custom and the commander’s preference than any legal authority.

A note in the 1819 edition of Nories’ Maritime Flags of all Nations reads as follows:’ The red ensign is the only one allowed to be hoisted on board Merchant ships; but in case the said ensign be much torn, and is being repaired, or a ship be at sea, without having one on board, then a blue, or St. Georges (i.e. White) ensign may be hoisted, provided it has a red border of the following width, at the top, bottom and fly end. For 800 tons and upwards, not less than 14 inches border. All ships under 800 tons burthen, 9 inches border.’ (It is worth noting that a portrait of the Cornish vessel Spackman, illustrates the use of a blue ensign, at least in the spirit of this alternative; as early as 1795 she is shown entering Naples flying such an ensign with a red border along the bottom.) So it seems that the circumstances given in Nories were not closely followed and were seen as little more than excuses to display a status symbol.

Although the style and technique in this portrait is generally similar to that in the portrait of the Swiftsure, the artist has taken a different approach to the subject. This time the Packet is shown in the process of shortening down the topgallants and jib. The result is that the sails provide a greater variety of shapes, those of the topgallants being closely derived from Ange-Joseph Antione Roux 1765 – 1835. (See his painting of the American ship Ulysses painted in 1804). The courses are brailed up as before but are still full of wind unlike those of the Swiftsure that might be hanging in a calm. In this painting the artist has used wetter washes, particularly in the sky, which has allowed softer modelling to the clouds. Similarly. the sea is handled less precisely than in the Swiftsure painting, the waves being ‘lumpy’ rather than rippling. Again the approach tends to be mechanical but the run of the waves around the hull is artfully managed to suggest the forward motion of the vessel. A few crew members can be seen including one standing in the chains to cast the lead; an appropriate activity in view of the precise description of the caption. A group of figures are shown forward who may be engaged in preparing the anchor but there are none to be seen on the quarterdeck. The general effect is to produce a more atmospheric and lively picture suggesting the activity and excitement as the vessel approaches port. By contrast the painting of the Swiftsure, with its more precise draughtsmanship and style conveys more authority as an accurate representation of the brig.

The painting shows a brig at anchor in Valletta’s Grand Harbour with a pendent at the main and flying a signal flag at the fore-mast head. It appears to be a red St. Georges cross on a white flag. If so it represents the Packet Duke of York.