PZ.594 Prima Donna

1 March 2023

When Falmouth avoided a big bang

15 March 2023When Falmouth Escaped a Big Bang

A chance remark in a recent funeral eulogy in Chepstow – ‘Family tradition has it he helped blow up a ship off Cornwall: we do not know where, when or why’ – uncovered an eye-witness account of a shipment of dodgy explosives that could have proved fatal for a large number of people, and perhaps even parts of Falmouth, back in 1972.

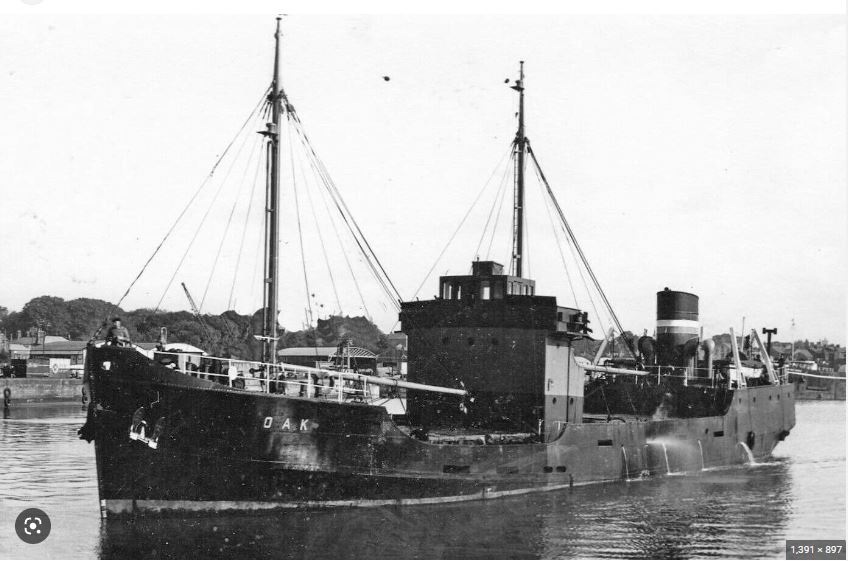

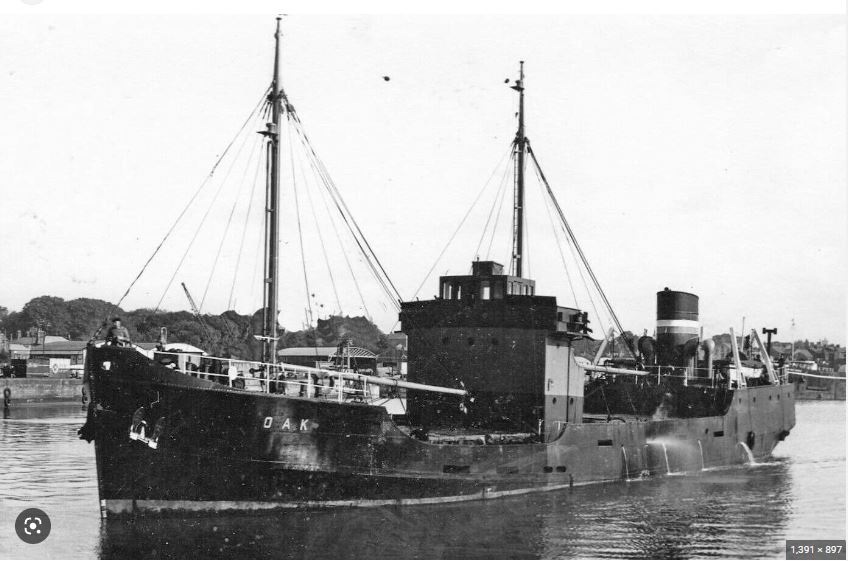

The story starts in late January 1972 when the 357 ton St Bridget – the epitome of Masefield’s ‘dirty British coaster’ – set off from Irvine in Scotland, loaded with a cargo of 370 tons of explosives produced by ICI. The cargo was destined to be trans-shipped in Falmouth to the 7,704 ton Blue Funnel cargo ship Autolycus for delivery to Manila.

Both ships arrived in Falmouth on Saturday 5th February.1 As was usual with vessels carrying or transhipping explosives, they were moored in the Cross Roads designated explosives transhipment anchorage, north of the Vilt buoy, in the northern part of the Carrick Roads.2

All went well with the cargo transfer but then, on Sunday 6th, people started to complain of headaches, a warning sign that nitro-glycerine was leaking. Alarm bells were rung and a series of ‘experts’ descended on Falmouth: Nobel Industries (a branch of ICI), The Home Office Explosives Inspectorate and representatives of the DTI.

A week of tension

There followed a fairly frantic few days. The West Briton reported:

Weeping Explosive Alert at Falmouth

The final phase was being played out at Falmouth yesterday in a tense drama in which it had been feared that a 140-ton cargo of high explosives might detonate prematurely.3

The drama in which about 90 men, three ships and several smaller craft were involved began on Monday in Carrick Roads, the deep-water berth of Falmouth’s outer harbour.

Gelignite was found to be “weeping” as cases were being transferred from the 965-ton coaster St Bridget to the 5,691-ton freighter Autolycus.

Some dockers who were moving the cargo and two ships’ officers complained of headaches – a warning of nitro-glycerine fumes.‘Move Out’ order

Falmouth’s harbourmaster Capt. Frank Edwards ordered the ships to leave harbour. They moved well out into the bay.

A Home Office inspector and experts from the Imperial Chemical Industries travelled to Falmouth overnight.

The St Bridget’s cargo came from ICI’s factory in Ayrshire and was loaded at Irvine.

The Autolycus outward bound from Liverpool was taking delivery at Falmouth as part of a general cargo for Manila.

In the danger zone were 15 dockers, about 50 men in the crews of the two ships, others from the pilot service, Customs and the harbourmaster’s department, as well as the experts.Declared Safe

The West Briton and Cornwall Advertiser, Thursday 10 February 1972

By Tuesday evening the experts had decided that the cases of explosives were safe enough to handle and the ships were permitted to re-berth in Carrick Roads.

Yesterday, the 698-ton coaster Lady Roslin, with a crew of ten, joined the other ships. She was called to Falmouth by radio as she returned from Zeebrugge after discharging explosives.

Work then started on transferring the cases to the Lady Roslin for return to Scotland.

Having completed cargo operations, the Autolycus, with its smaller-than-expected cargo of safe explosives, was able to set sail for Singapore late on Wednesday 9th. This left two cargoes: the weeping load and another consignment which appeared safe. The decision was made to transfer the faulty explosives back into the St Bridget which would then be disposed of at sea.

A first-hand account

At this point, we can return to the eulogy. A few days after the funeral, a tape emerged amongst the deceased’s effects. It features a Mr Francis Tate of HM Explosives Inspectorate dictating a draft report of the incident.4

He picks up the story on Saturday 12th:

… Following this meeting I accompanied Mr Stenhouse of ICI to the St Bridget and we laid an appropriate cordtex web5 yielding a system was such that there were five cordtex leads each capable of independently detonating all 20 primers placed in the cargo.

I hope that ICI now know that they might have to pay £93,000 in compensation for the St Bridget.

Sunday 13 February 1972

The day started with the ships notionally prepared to go and ICI making attempts to acquire a fast launch and to lay on the use of a tug. Early in the morning the 50 tons of conventional cargo was removed from the Lady Roslin into a lighter so that she was also ready to act as escort vessel and we heard from the Navy that a destroyer would be made available to act as guard ship. A position was quoted such that there should be no difficulty in reaching it given six hours of reasonable weather.

There was some nervousness amongst the crew about being on board a ship filled with leaking explosives for six hours but Tate assured them:

… that the hazard from the cargo on the St Bridget as presently stowed was not one that should cause them alarm and [I] told them that both Mr Stenhouse and myself would be accompanying them when the ship moved out of harbour.

There were other details to arrange, however,

Captain Stephenson and his DTI staff stated that they had acquired a portable radio and transmitter/receiver devices from the coastguard so that adequate communication could be assured. On this day I permitted the representatives of Messrs Bush and Messrs Marconi to remove the large radio and radar equipment from the St Bridget. They were however instructed not to use any type of flame cutting equipment and to confine their activity strictly to the bridge.’

At the time, the radio equipment would have been on hire from Bush and Marconi.

The weather forecast at the end of the day was not particularly promising but ICI had laid on the use of a harbour tug if necessary and were negotiating for the use of one of two fast speedboats. The Roslin was empty and in a position to act as escort and the Bridget was ready to sail.

By Sunday night, everything was in its appointed place. The St Bridget held all the leaking explosives; the lighter held the safe explosives and the Lady Roslin was on standby to act as a support vessel.

On the following day

Monday 14th February – St Valentine’s Day

At 7 o’clock in the morning we observed the weather conditions appeared to be fine and at about 9 o’clock we received assurance from the forecasters and from the Wolf Rock lighthouse keeper that sea conditions were such that we would be justified in setting sail. At this time Mr Stenhouse and myself cut the necessary length of slow fuse to give a 32 minute delay and carried out tests to ensure that the burning rate was correct. We boarded the St Bridget at about 11 o’clock and the Lady Roslin and St Bridget set sail at about 11.15. There had been a short delay while the final arrangements were made for the escorting launch but this followed us after we had left harbour.We reached the appointed spot for the destruction of the Bridget at about twenty to five. The Lady Roslin carried a Decca navigator and thus we were able to pinpoint the position exactly. A considerable sea swell had built up and there was some difficulty in evacuating the crew but they eventually got off the boat at about ten past five.

The captain,6 Mr Stenhouse and myself remained and Mr Stenhouse and I arranged the fuses. These were triplicated to ensure complete reliability and were so connected that the ends led to the side of the ship. We had also arranged a warning charge of about 50 ft of cordtex on a reel which we intended to give a five minute warning of the detonation.

At this point proceedings were held up for about a quarter of an hour because a light aircraft which we later learned belonged to ITN insisted on circling directly over the ship. We thought it unwise to actually start lighting fuses at this time and eventually we were able to contact the Navy and the aircraft flew to a reasonably safe distance.

At about twenty to six I, Mr Stenhouse and finally the captain left the ship, passing into the launch alongside and a miner’s portfire7 was used to ignite the four fuses. There was considerable movement between the launch and the ship and we had some difficulties at this time, nevertheless we were able to fire the fuses on the main train. Although we probably could have fired the warning shot as well we did not wait to do so as the relative movement between launch and ship was becoming very marked indeed and in fact the bows of the launch and its sides had been quite badly knocked about during this manoeuvring. For this reason there was no warning charge fired.

The launch carried us to the Lady Roslin which was at this time about a mile and a half away and Mr Stenhouse and myself transferred to that ship. The launch then headed for home while the Lady Roslin went to a distance of three miles from the St Bridget.

The explosives in the St Bridget detonated at 6.17. The light failed for recording purposes some five minutes before the detonation of the St Bridget but we were able to get clear visual sight of the explosion. There is no doubt at all that this was a general one and that the whole of the explosive cargo blew at once with an extremely bright flash and even at three miles there was an appreciable concussion wave.

Another eye-witness was Clifford Rolling, the owner and engineer of the Amron, the motor launch ‘which carried explosives technicians to the St Bridget and then took them and the ships’ crew away to safety’. He told the Falmouth Packet:

The St Bridget anchored at a predetermined spot and the Amron took off five crew members. This left the skipper and two explosives experts aboard.

Falmouth Packet

We went off while the explosives people laid the fuse right around the St Bridget – on the deck.

When they were ready we went alongside again. They brought the end of the fuse aboard the Amron, lit it and then we took off like bats out of hell.

We were three-and-a-half miles away from the St Bridget when she blew. There was a great crack, flash and a huge pall of smoke. The last time I saw anything like that was on Christmas Island when they blasted the atom bomb.

Another account reports that:

Saint Bridget did not immediately sink and the destroyer HMS Caprice which had been acting as a safety vessel keeping ships well away from Saint Bridget, used gunfire to make the cargo vessel sink.

History of J & A Gardner and Co Ltd – the owners of the St Bridget.

An account from a former student of Plymouth Nautical College confirms the presence of destroyer but curiously makes no mention of the gunfire:

I was one of a group who were invited to join an RN ship for a day at Plymouth. We boarded this vessel, an oldish destroyer I think and I believe the last of her type, down at Devonport one morning and sailed out into the Channel, where we spent the next few hours policing an exclusion zone around what I believe was a small coaster. Apparently she’d arrived in port with a cargo of (or including) explosives, which were weeping and had been deemed unstable. Anyway, at dusk there was quite a vivid flash on the horizon as that little ship was blown asunder, followed a few seconds later by the shock wave. A few bits of timber marked the spot where she’d been, and then it was full speed back to port.

Former student of Plymouth Nautical College

It is hard to believe that the Bridget needed any additional gunfire to finish her off, given the amount of explosives she had been carrying. Does the mention of a ‘few bits of timber’ suggest that HMS Caprice closed to the actual site to ensure that she had gone down of was that poetic licence? (Remember it was after dusk). Either way, could it have been that the captain of HMS Caprice saw an opportunity to fire her guns one last time before she was taken off to her final berth?

Mr Tate completed the story of the day:

The Lady Roslin then returned to Falmouth and on the way we were able to watch […] on the television saying that that […] was wrong and there can’t have been anything wrong with the explosives because ICI never made that kind of explosives.’

Two days later, the remaining explosives were transferred from the lighter to the Lady Roslin who set off for Irvine to return them to ICI.

The designated site for the explosion was 40 miles south of the Lizard at 49° 25.7’N, 5° 3.7’W. The depth in that area was around 80-90m. Modern charts show a wreck peaking at around 62m.

Coda

Mr Tate went on to praise those involved although we might question the ‘almost’ in the first sentence:

It is my opinion that almost all the parties concerned in this exercise came out of it with great credit.

ICI while they obviously were at fault in the manufacture of the original explosive, met the emergency conditions with great resource and with commendable speed and did not flinch at spending what must have been even for them a considerable amount of money for no return other than that of ensuring public safety.

Captain Edwards the Harbourmaster at Falmouth who was badgered by the press constantly in the early stages of the operation was obviously very cool indeed and was most helpful and cooperative in what must have been to him a most trying situation.

Captain Fitzgerald of the Autolycus while justifiably incensed that anyone should put sub-standard explosives on his ship was extremely courteous and helpful not only to myself but also to the ICI representatives who were dealing with the actual problem which this raised.

Captain Stephenson and his staff from the DTI were able to arrange the necessary facilities with remarkable speed and efficiency.

It is my own opinion that the hazard arising from nitro-glycerine exudation from the bulk of explosive of this size could not have been more expeditiously dealt with and that the delays which did exist were those occasioned by the need to make proper examination such as would ensure that ships were not blown up indiscriminately and wholesale and that no group of persons was exposed to excessive risk.8

He summarises the issues and causes:

… the material was faulty in at least three ways:

● The actual explosive exuded nitro-glycerine which was most undesirable and was in fact in breach of the conditions under which the explosive was to be manufactured

● The sealing of the polythene bags used to contain the explosive was obviously inadequate

● … It was found that very long staples had been used before sealing the top of the box to the wooden sides and that these staples were so angled that they had penetrated both layers of the polythene wrappings. We therefore had a position where first of all the polythene wrapping was not impermeable and secondly we had metal staples in some cases actually embedded in the explosive cloth positionThe conditions in which explosives were being transported in the St Bridget were also most unsatisfactory. I am not at all clear how far the Blue Book conditions apply to coasters engaged in home trade but … the conveyance of bulk explosives in an unprotected metal hold with dirty plank floors contaminated with coal and scrap iron is most undesirable even when the explosive concerned does not exude nitro-glycerine.

In the case of the Autolycus in which adequately clean conditions were found it was possible to deal with the problem of the leakage simply because the working conditions were such that there was no excessive hazard arising from steel grit and like contamination. There is little doubt in mind that had the Bridget been appropriately fitted out with even a notional wooden cladding in the explosive carriage area and had it had a close-boarded floor which could have been swept clean, it would still be afloat today and the explosive could have been trans-shipped to some vessel such as a lighter which obviously would have been a much cheaper exercise than was the one actually carried out.

The above points all need further investigation and in the case of the last one, it would appear that we should have conversations with the DTI about conditions under which explosives traffic in coastal shipping is permitted.’

The following Thursday the West Briton summarised the events of the week:

Danger Cargo Blown Up – Plus the Ship

A 960-ton coaster and 110 tons of nitro-glycerine went up in a big bang 40 miles off The Lizard on Monday.

The nitro-glycerine was part of a 370-ton cargo of high-explosives which the coaster – the St. Bridget – brought from Imperial Chemical Industries’ factory in Scotland last week to be loaded into other ships.

This part of the cargo was found to be “weeping” – an indication that it could explode prematurely.

Falmouth dockers were transferring some of the cargo to the 5,691-ton freighter Autolycus to be shipped to Manila when the danger became apparent.Declared Unsafe

The West Briton and Cornwall Advertiser, Thursday 17 February 1972

The experts found that although the nitro-glycerine was in no immediate danger of exploding, it was unsafe to transport to Scotland. It was unfit for reworking in the ICI factory. Continued handling could have added to the danger.

When conditions were reasonably calm on Monday, the St. Bridget put to sea in charge of members of her own crew.

An ICI demolition expert set some fuses in the St. Bridget’s cargo for that big bang.

HMS Caprice, a destroyer, patrolled the area. Land’s End radio warned other ships to keep clear.

An unanswered question

The audio tape which forms the core of this article was found amongst the effects of John Poyntz who died in January 2023, aged 96. He, like Francis Tate, worked for HM Explosives Inspectorate, was much the same age and joined the Inspectorate at about the same time. It is unclear whether he was present at the sinking – he is not mentioned in the report – or whether the ‘family tradition’ mentioned in his eulogy grew out of his knowledge of the events rather than his practical participation. Why had he held onto the tape?

Note: The author is grateful for assistance from experts on some of the technical aspects of this article.

- Fox’s Arrivals and the Harbour Master’s Register of Arrivals

- Unless otherwise noted, the main sources for this article are the Harbour Master’s records: the Register of Arrivals, the Journal, and the Minutes of the Harbour Committee and Harbour Commissioner’s Meetings

- Figures for the quantity vary between the different accounts, perhaps because the assessment of what was safe and what was dangerous was changing as the cargo was inspected and moved

- This tape, held by the family of the deceased, used a legacy system and is of poor quality. The following extracts have been edited accordingly. We have not been able to track down a copy of the final report

- Cordtex – a brand name for a form of fuse generally used in mining

- Captain Coomicon

- A device for lighting a fuse train

- His failure to mention Captain Coomicon of the St Bridget may be related to his later explanation of the conditions on board: see below