Motor Yachts

16 April 2019

Operation Ariel and Falmouth – June 1940

20 April 2019Operation Ariel (Aerial) and the Evacuation from France – June 1940

Operation Ariel was the code name for the evacuation of troops and civilians from the western ports of France from 15th to 25th June 1940. Although Operation Ariel was of similar size to Operation Dynamo, which rescued the British Expeditionary Force and other allied soldiers from the beaches near Dunkirk, it has never achieved the same degree of prominence and importance in the public consciousness despite its vast scale.

Winston Churchill described Operation Dynamo, carried out by the Royal Navy, merchant vessels and the “little ships”, as ‘the miracle of deliverance’ and the Admiralty signalled the evacuation as being complete on 4th June 1940.

However, ‘the miracle’ was not over as many British and allied troops were left in France. Some were combat units such as the British Highland Division, others were support and line of communication troops, together with RAF ground staff, medical personnel and embassy and consular staff. There were also Polish and Czech troops and airmen together with a considerable number of civilian evacuees and refugees.

Once again there was a need for a large scale evacuation by sea from the western ports of France, first by Operation Cycle from Le Havre and then by Operation Ariel from ports such as St Nazaire and Bordeaux.

Paris fell to the advancing German army on 12th June and by 14th June two thirds of France was occupied by the Germans. By 17th June the French, under Marshal Petain, had decided to ask for an armistice and on 22nd June the French surrender was signed.

Initially Headquarters in England had been reluctant to accept the need for a second evacuation from France but when it became obvious that France intended to make peace with Germany the War Cabinet made it a priority to extricate forces and other personnel as quickly as possible. After the fall of Paris, Operation Cycle was immediately put into place by the British government to carry out evacuation from Le Havre. This first attempt was only partially successful, hampered by fog and heavy shelling, but by 13th June over 15,000 troops had been saved.

Operation Ariel which followed was a much larger undertaking lasting from 15th to 25th June involving the Royal Navy destroyers HMS Havelock, HMS Wolverine, HMS Beagle, HMS Highlander and HMS Vanoc with over 130 British and allied liners, merchant ships, motor vessels and tugs. The operation was coordinated by the Royal Navy with Admiral James, C-in-C Portsmouth, commanding the evacuation from Cherbourg and St Malo, and Admiral Dunbar- Nasmith, C-in-C Plymouth and the Western Approaches, commanding the evacuation from Brest, St Nazaire, La Pallice and other ports on the Gironde estuary.

The vessels were dispatched from and returned with the evacuees to various English southern and western ports. As one of these ports, Falmouth, was heavily involved and over the duration of Operation Ariel more than 6,000 allied troops, other evacuees and refugees and a variety of interesting cargoes were landed there.

Vic Angove, who was 12 years old and living in Sea View Cottages, Falmouth, recalled this happening in his memoir “Challenges” written in 2001.

Boats of every description were coming across the Channel filled with service personnel and civilians escaping to freedom. The Falmouth Bay was filled with vessels. Mr Richmond (a neighbour) was still able to get fuel for his launch and he took Bryan (Vic’s twin brother) and myself with his family to the Bay. We were amazed at the number of vessels, all with their decks filled with people, desperate to be safe. The following day the town soon became crowded with soldiers, sailors and civilians. They were so tired and hungry that is one memory I will never forget. Mother had made pasties for tea, but when we went to the High Street and saw the state of the soldiers laying anywhere they could find, Mother went home and made cups of tea, took the pasties from the oven and gave them to the soldiers who were really exhausted. All the neighbours helped in whatever way they could as these members of the British Army had been without rest for so long.[*]

Charles Ernest Cundall 1940/IWM

At this time Miss Evelyn Radford, a well-known figure in Falmouth who was involved in the arts in the town, volunteered to help with the influx of evacuees at the Princess Pavilion and kept a diary of the dramatic events that happened in June 1940.

Thursday, June 20: What a mix-up, civilians of all sorts, British subjects with remarkable English or none at all, French subjects speaking English perfectly, Malays with no known language, a sprinkling of Spanish republican survivors, Polish Red Cross, Czech airmen, French and British all services, War Graves Commission, Imperial Airways, Standard Oil Co., Women’s Auxiliary drivers, a young woman with several children and twin babies of five weeks. They pour in steadily.

Friday, June 21: More boats arrived. The harbour crowded like the Golden Horn .[*]

The evacuation from western France was a tremendous undertaking involving complex planning and co-ordination by the Royal Navy. Vessels were sent from the southern English ports of Portsmouth, Southampton, Poole, Weymouth, Plymouth and Falmouth.

The Royal Navy sent 102 ships and 45 requisitioned Dutch coasters and the Merchant Navy contributed 129 passenger ships and 141 cargo ships (including some vessels from allies such as Belgium and Poland). During the operations, RAF fighters from 1, 17, 73, 242 and 501 Squadrons provided air cover against Luftwaffe attacks.

Tens of thousands of British, Polish and Czech troops were rescued together with civilian evacuees and refugees and although much equipment was lost a considerable amount was recovered and embarked onto some of the ships alongside evacuees.

With such a vast and complicated movement of vessels and personnel many individual stories arise but of many that involved a connection with Falmouth, three instances and four ships demonstrate the significance of Operation Ariel.

The SS Broompark, French Heavy Water and Belgian Diamonds

The SS Broompark was launched in October 1939, registered in Greenock and operated by the Denholm Line. The master was Captain Olaf Paulson who was born in 1878 in Christiana, Norway but had lived in Leith in Scotland from a young age and had taken British citizenship in 1904.

The Broompark entered Bordeaux harbour with a cargo of coal on 13th June 1940. Paris had fallen the previous day and Captain Paulson then agreed to take part in the evacuation of refugees from the port back to England.

There were various groups of passengers on the ship’s return to England. Captain Paulson’s log does not give details of passengers but mentions that there were 101 souls on board. However other sources state that amongst those on board were Charles Howard, Earl of Suffolk and Berkshire, British Scientific Liaison Officer in Paris and Major Ardal Golding, a mechanical engineer and an officer in the Royal Tank Regiment, who had worked closely with Howard in Paris. They were accompanied by their secretaries and by 33 French scientists, engineers and technicians who they had been commissioned to evacuate to England. This group included Hans Von Halban and Lew Kowarski, physicists from the College de France and Professor Joseph Cathala, a chemist from the University of Toulouse, who had all worked closely with Professor Frederic Joliot-Curie on the development of ‘heavy water’ and nuclear energy.

There was also a group of Belgian officials, bankers and people connected with the diamond trade. Paul Timbal, managing director of the Antwerp Diamond Bank, was one of these who escaped from Belgium and the advancing German army in May 1940 entrusted with a fortune in diamonds.

A variety of military personnel also sailed with the ship. This included a detachment of RAF ground forces commanded by Major Golding and a number of French and Polish officers. Other civilians such as wives and families of some of those mentioned, of British officers and consular officials in France accounted for the rest of the passengers.

The cargo was made up heavy water, diamonds and machine tools. The heavy water (deuterium oxide) was an important component in the process of producing nuclear energy and had originally come from the Norsk Hydro hydroelectric plant at Ryukan in Norway, which was the only place where it could be isolated at the time. In 1939 the plant was receiving increasing orders from the German chemical company I.G.Farben and alerted to the dangerous potential of such a demand, Lieutenant Jaques Allier, an agent of the Deuxieme Bureau, spirited the entire stock of 185 kilograms in 26 drums out of Norway and eventually it reached France. When France was invaded Professor Frederic Joliot-Curie took charge of the material, storing it in a vault at the Banque de France, then in a prison and then taking it to Bordeaux. Eventually it was embarked on the Broompark with the scientists and technicians evacuating to England.

The diamonds brought from Antwerp by Paul Timbal, managing director of the Antwerp Diamond Bank, passed through Belgium then into France. After keeping ahead of the advancing German army he and the diamonds eventually reached Bordeaux on 16th June. He approached the British Consulate and with his family was given tickets for embarkation on the Broompark. The value of this cargo was between £1,000,000 and £3,000,000 and he was told by the Consul that the ship would have a British military guard with anti-submarine and anti-machine guns.

The machine tools amounted to approximately 600 tons and consisted of airplane motors for the French Air Ministry which had arrived from the US and had been left in railway wagons on the quay. Captain Paulson, the Earl of Suffolk and Major Golding loaded these on board together with about ten cars belonging to passengers.

The Earl of Suffolk, Major Golding, Paul Timbal and the ship’s carpenter also built a raft and anchored the two crates of diamonds and the heavy water drums to it. The rationale behind this move was that if the ship sank the raft would float and the cargo would be saved and according to Paul Timbal;

It was not so much the value of our treasures that was important, but the use the enemy could make of them. If we succeeded in saving them it would be like winning a battle over the enemy![*]

SS Broompark left Bordeaux without the assistance of tugs on 19th June and sailed down the Gironde towards Royan and then continued unaccompanied out to sea. She reached Falmouth overnight on 21st/ 22nd June. The Harbour Master’s log states that the ship was anchored in the Bay awaiting instructions and carrying refugees and machine tools.

A launch with naval officers arrived and the Earl and Paul Timbal went ashore to discuss matters with the Port authorities. The passengers and the cargo were finally disembarked at the pier about 10pm on Saturday 22nd June. They were taken by buses to the railway station where a special train was waiting. The heavy water and the diamonds were locked in the mail van under armed guard and the train took the passengers and the cargo overnight to London.

On arrival in the capital the heavy water was taken under armed military guard to be stored, first at Wormwood Scrubs prison and then on to the Cavendish Laboratories in Cambridge. The diamonds were also taken under guard and delivered by Paul Timbal to the Diamond Corporation at 8 Charterhouse Street, London.

The SS Chorzow and the Polish National Treasure

Kyzystof Jozef Werner (before 1794)

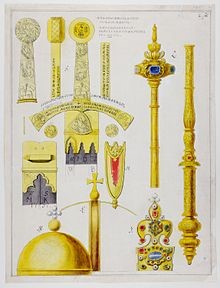

The Polish National Treasure was a collection of objects of historical or artistic value evacuated from Poland in 1939. A large part of the treasure came from the collection at Wawel Castle in Krakow together with objects from the Royal Castle, the National Library in Warsaw and the library of the Catholic Higher Seminary of Pelpin.

The treasure included Szczerbiec, the jewelled medieval coronation sword of Polish kings together with other jewelled coronation regalia and hundreds of other pieces in gold and silver. There was a two volume Gutenberg Bible, various precious books and religious manuscripts of historic interest, thirty six original Chopin compositions and thirteen pieces of his correspondence. Also there was a collection of one hundred and thirty seven C16th Flemish tapestries considered to be masterpieces of the art and Europe’s finest.

As the threat of invasion of Poland from the German Third Reich became more pressing the Polish Government made the decision to move the treasure across Europe to safety. The treasure was packed into specially constructed cases and cylinders and two days after Germany invaded Poland on 1st September 1939 they were secretly transported across the border to Romania under the care of Josef Polkowski and Stanislaw Zaleski, two of the curators from Wawel Castle.

Efforts were made to secure the safety of the treasure in Switzerland and Vatican City but these were of no avail. Therefore, after being transported by rail to Constanza on the Black Sea and then by sea through the Dardanelles into the Aegean Sea, the treasure reached Malta where it was kept for two weeks. The Polish government in exile in France then requested that the treasure be relocated to Aubusson in France where it was stored in a disused factory. This hiding place only lasted for six months until the Germans began their advance into Western Europe.

On 19th May 1940 the custodians decided that the treasure was no longer safe in France. The Polish government in exile in France charged Dr Karol Estreicher, an eminent Polish art historian and secretary to the Prime Minister in exile, General Sikorski, with the task of taking the treasure from Aubusson to Britain. He and the custodians prepared the cargo for travel once again to Bordeaux with a view to evacuation by sea to England.

On arrival in Bordeaux with a lorry loaded with the treasure, Polkowski and Zaleski approached the Polish consulate and explained the situation. The SS Chorzow a Polish ship was in the port and the master, Captain Zygmunt Gora, was asked to come to the Consulate.

The Chorzow was a small steamer built in 1921 in the Netherlands which became part of the Polish merchant fleet in 1930.

At the outbreak of war in 1939 she was in Gothenburg and it was decided by the Polish government in exile that all the Polish ships in Sweden and Norway should be sailed to Britain and in October a convoy of such ships including the Chorzow, left Bergen in Norway for Rosyth accompanied by a Royal Navy escort.

In June 1940 the Chorzow had carried coal from England to Bordeaux where she was requisitioned to assist with the evacuation. Captain Gora had already embarked over one hundred and ninety Polish airmen when he was called to the Consulate and told of the situation regarding the treasure. Immediately, without further discussion, the master climbed into the lorry and directed it to the port where it swept through the dock gates past the security guards to the ship. The crew were told to transfer the treasure from the lorry to the hold of the ship and this was done as quickly as possible. The ship was overcrowded with the troops and other refugees and the trunks and cases holding the treasure were used as tables, chairs and even beds during the voyage.

The Chorzow sailed in the tail of a large convoy from Bordeaux and Le Verdon on 15th June. At midnight off La Rochelle the ship next to the Chorzow suffered a direct hit by a bomb and was badly damaged. Despite the fact that there was no further action during the night, the next morning Captain Gora decided to leave the convoy and make his way to Falmouth alone.

The ship reached Falmouth with no other interference on the 21st/ 22nd and was listed as anchored in the Bay awaiting instructions on the 22nd in the Falmouth Harbour Master’s Log. The ship docked on the 22nd and at midday two buses took the military and civilian refugees into the town. The custodians of the treasure stayed to guard the treasure and when an officer from the Admiralty arrived at 5.00pm to redeploy the ship, the Captain refused to do so until the treasure was safe. Despite efforts by the Customs and Port Security officers the custodians of the treasure also refused to cooperate with the authorities and reveal the contents of the various cases and cylinders. The Polish Embassy in London was informed and a security plan was put into place.

EJ (Bob) Dunstan a journalist with the West Briton was involved with the Intelligence Service and Port Security at Falmouth at the time. He left this account of the arrival of the treasure amongst his papers which his widow contributed to the WW2 People’s War Archive in 2005.

One group of Poles arrived in a Steamer with art treasures of their country crated up – these they refused to open or allow anyone else to do so. They declared they had been bidden to guard these with their lives – and were prepared to sell their lives to keep that promise. Customs and Security Officers failed to budge them in their resolve and finally contacted the Polish Embassy in London, who sent down representatives to arrange the transport to safe keeping of the works of art.[*]

A railway freight car was secured and loaded by dock workers under close supervision and guard. It was taken to the station and attached to a passenger train leaving for London. It was accompanied by the custodians and guarded throughout the journey. On arrival in London it was met by representatives of the Embassy and taken into the Embassy’s premises and care where it remained until July while plans were made for the treasure to be transferred for safe keeping to Canada. On the 1st July the treasure was transferred to Glasgow and embarked at Greenock on the SS Batory, She was a Polish transatlantic liner and flagship of the Polish Merchant Marine and had been used by the Allies in Operation Aria, accompanied by a convoy of heavily armed Royal Navy vessels she left for Halifax, Nova Scotia on the 4th July and arrived safely on 12th July.

The treasure remained in Canada for nearly twenty years after WW2. The communist government, which took over in Poland in 1945, and the Polish government in exile both made competing claims on the treasure and it was not until 1961 and a change in the regime that the treasure was finally returned to Poland.

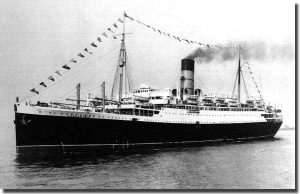

The SS Oronsay, the sinking of the His Majesty’s Transport Lancastria and the artist Charles Pears

HMT Oronsay in the foreground with Lancastria sinking on the horizon.

Charles Pears, PMSA, ROI

In June 2017 various news reports appeared concerning a painting of the SS Oronsay which had recently been discovered in Australia by Jamie Rountree, director of the Rountree Tryon gallery in London. The painting by Charles Pears, a marine painter and official war artist in both World Wars, shows the evacuation of St Nazaire on 17th June 1940 as part of Operation Ariel. The focus of the painting is on the SS Oronsay but the HMT Lancastria is seen sinking on the horizon.

More than 4,000 people died in the sinking and the tragedy remains Britain’s worst maritime disaster. More lives were lost than the sinking of the Titanic and the Lusitania combined, and fearful of the damage to morale a news blackout was imposed at the time by Winston Churchill. Reports and images of the sinking were condemned to official secrecy and to some extent this state of affairs still applies today. The emergence of the painting as a representation by a contemporary artist is, therefore, a significant find in the story of the tragedy.

Charles Pears 1873-1958 was an artist who was born in Pontefract, Yorkshire. He studied at East Hardwicke and Pomfret College and became commercially active from 1890. He spent a considerable part of his career in London and the South of England eventually moving to St Mawes in Cornwall. He was an illustrator, a poster artist, a lithographer and graphic designer and an important marine painter. He was the first elected president of the Royal Society of Marine Painters and a writer of books on yachting and cruising. He served as an officer in the Royal Marines in the First World War and as an official War Artist in both the First and Second Wars. The vast majority of his output from this time is held in the collections of the Imperial War Museum and the National Maritime Museum.

The picture of SS Oronsay taking part in Operation Ariel was possibly privately commissioned for the Captain and the background view of the sinking Lancastria is one of the few images of the incident which was probably informed by eye witness accounts from survivors many of whom were brought in to the ports at Plymouth and Falmouth.

SS Oronsay was built as an ocean liner by John Browns of Clydebank for the Orient Steam Navigation Company and launched in 1924 and named for one of the Hebridean Islands. Her maiden voyage began on 7th February 1925 from London to Melbourne, Sydney and Brisbane and she continued on the passenger route to Australia until 1940 when she was requisitioned as a troopship by the British government.

She then took part in the Norwegian campaign and was involved in Operation Alphabet and the evacuation of troops from Narvik to Scotland on 7th June 1940. Almost immediately the ship was re-deployed as part of Operation Ariel and according to the Falmouth Harbour Master’s Log the ship arrived from Glasgow on 15th June in Falmouth to be given orders for St Nazaire. Oronsay arrived in the Loire Estuary early on 17th June and immediately began embarking troops, ferried out from the port in destroyers and small boats. During the embarkation the vessel was anchored near the Lancastria and about 13.00 hours came under attack from the air by German dive bombers. She was hit several times and there was a direct hit on the bridge killing several people and destroying the chart room and communication and other navigational equipment. The nearby Lancastria was also hit and rolled over and sank within twenty minutes with great loss of life.

Some of the survivors were rescued and transferred into other vessels including the Oronsay which although badly damaged was still seaworthy and which left for Plymouth. The Captain of the Oronsay, Arthur Nicholls, assisted by his Staff Commander Ivan Goldsworthy, brought the ship back to Plymouth in a feat of seamanship without any instruments or charts. In October of 1940 The London Gazette reported that Captain Arthur Edward Nicholls, Master of SS Oronsay was to be made a Member of the Order of the British Empire and Ivan Ernest Goodman Goldsworthy, Staff Commander of SS Oronsay was to receive a Commendation, for bravery and seamanship during the incident.

The transport “Oronsay” was engaged in withdrawing troops from France and rescued a large number of military officers and other ranks, many of whom proved to be survivors of H.M.T. “Lancastria”. “Oronsay” was heavily attacked from the air and hit at the moment of her arrival at St Nazaire. The embarkation took some four or five hours during which five bombing attacks were made upon the vessel. Captain Nicholls was ably assisted by Staff Commander Goldsworthy who had been injured. The Master’s resource and coolness were outstanding and he brought the ship home without any bridge instruments or charts.[*]

In August, after repairs, the ship resumed her wartime duties sailing from Liverpool for Halifax with 351 evacuated children. In October the ship was part of a convoy carrying troops from the Clyde to Egypt which was attacked by Luftwaffe aircraft off Ireland. Oronsay suffered blast damage to her engines and was left behind without escort by the others in the convoy. Fortunately the engines were restarted and she was able to make her way back to port but with a number of casualties on board.

The end came for the ship in October 1942, while sailing unescorted from Cape Town to the UK carrying RAF personnel and a cargo of copper and oranges, she was torpedoed and sunk by the Italian submarine Archimede some 500 miles off Liberia. Six crew members were lost but the remainder of those on board, about 350 passengers and crew, were able to escape in the ship’s boats. Most of the survivors were rescued after twelve days by HMS Brilliant and the rest by the Vichy French and interned at Dakar. Captain Norman Savage, Master, was awarded the CBE and Captain Richard Roberts, Staff Commander, was awarded the OBE in April 1943 for their conduct and seamanship throughout this incident.

After WW2 the Orient Line launched a second SS Oronsay to serve the Australia route in 1950 which continued until the ship was eventually withdrawn from service in 1974 and broken up in 1975.

Royal Mail Ship Lancastria was a British Cunard liner built on the Clyde and launched in 1920 as the RMS Tyrrhenia. Her maiden voyage was made in June 1922 between Glasgow and Quebec City – Montreal. In 1924 the ship was refitted and renamed Lancastria and was used on routes between Liverpool and New York and as a cruise ship for the Mediterranean and Northern Europe.

In April 1940 she was requisitioned as a troopship and as HMT Lancastria was involved in Operation Alphabet, the evacuation of troops from Norway, which took place from late May to early June of that year. Almost immediately on 15th June the Lancastria, under the command of Captain Rudolph Sharp, was ordered to proceed to Quiberon Bay for onward passage to St Nazaire to take part with a flotilla of ships in Operation Ariel.

The ship arrived off St Nazaire on 17th June anchoring near to the Oronsay. Although the official capacity of the ship was 2,200 Captain Sharp had been instructed by the Royal Navy to,

“… load as many as possible without regard to the limits set down under international law.” [*]

By early afternoon at least 5,000 (some estimates give the figure as up to 9,000) troops and civilians had embarked on the Lancastria when the nearby Oronsay was attacked by German planes and suffered a direct hit which destroyed much of her bridge and chart rooms but left her seaworthy. At about 15.00 Captain Sharp was ready to sail but decided to wait for a destroyer escort. However before this could be arranged the enemy planes returned and the Lancastria was bombed at 15.58. The ship was hit by bombs which penetrated the holds, one bomb went down the funnel and detonated inside the engine room and the almost full fuel tanks were ruptured, spilling the burning oil into the surrounding sea. At 16.03 HMS Highlander signalled Command that HMT Lancastria was hit and sinking, rolling to one side and down at the bow. Within twenty minutes the ship had sunk taking with it the majority of those on board. Less than 2,500 survived and it was impossible to know how many were drowned but estimates range from 3,000 to as many as 6,500, all of which make it the largest loss of life in British maritime history.

Other ships involved in the evacuation, including the badly damaged Oronsay, began the rescue of survivors. Survivors reported being picked up from the water by a variety of vessels, sometimes after several hours, being covered in oil and machine gunned in the water by enemy planes. Oronsay returned to Plymouth with evacuees and survivors of the sinking. Other ships returned to various other ports in England and Miss Evelyn Radford recorded the first arrivals in Falmouth of survivors of the sinking.

Wednesday, June 19: First arrivals, a boatload of survivors from the ‘Lancastria’ torpedoed on her way home. Men, all sailors and soldiers, blackened and coated with oil, like the sea birds where oil fuel has been discharged. Rush for the canteen, the overflow lying out on the grass in the sun.[*]

At the time the full story of the sinking was never officially revealed. The D-notice system was used to suppress the news but the story was broken by the Press Association on 25th July. It was then taken up by The New York Times and The Scotsman to be followed by other British newspapers but due to the government’s suppression of the story and the secrecy imposed on the survivors of the incident the tragedy had become a largely forgotten disaster. However, over time the work of the Lancastria Association and other agencies have led to greater recognition of the event, the loss of life and the effects on the survivors. In June 2015 at Prime Minister’s Question Time, George Osborne, deputising for the Prime Minister, said of the sinking;

It was kept secret at the time for reasons of wartime secrecy, but I think it is appropriate today in this House of Commons to remember all those who died, those who survived, and those who mourn them.[*]

Conclusion

By June 4th 1940 the evacuation of allied soldiers from Dunkirk, Operation Dynamo, was complete. Although the rescue signalled a defeat it seemed like a victory and the Operation has taken a prominent place in the history of World War II. The second phase of the evacuation, Operation Ariel, from the western ports of France had still to be concluded. The ten days from 15th to 25th June 1940 involved a vast and complex movement of ships and the evacuation of many allied troops, civilian evacuees and refugees and much valuable cargo. The Operation deserves a far greater degree of recognition as does the port and town of Falmouth for the vital role it played in the history of such an evacuation and rescue.

REFERENCES

Books and Articles

Angove, Victor, Private Memoir, 2001

Draper, Alfred, Operation Fish, The Race To Save Europe’s Wealth, 1939-1945, London, 1979, Cassell.

Dunstan, E.J. Falmouth Port Security, Article for BBC, WW2 People’s War Archive.

Falmouth’s Wartime Memories, 1994, Arwenek Press.

Timbal, Paul, “Why the Belgian Diamonds never fell into enemy hands” May 10 – June 23”, 2014, Bruno Comer.

Sebag-Montefiori, Hugh, Dunkirk, Fight to the last man, London, 2006, Viking Press.

Stokes, Teresa, A Definitely Unpleasant Show, Article for BBC, WW2 People’s War Archive.

Swoger, Gordon, The Strange Odyssey of Poland’s National Treasures 1939-1961, A Polish- Canadian Story, Toronto, Ont, 2004 Dundum.

Electronic Sources

Lancastria Association of Scotland.

www.lancastria-association.org.uk.

Schwinghamer, Steve, Journey of Wawel Treasures to Canada, Historian Canadian Museum of Immigration at Pier 21, Blog May 24th 2013.

www.pier21.ca/blog/steve-schwinghamer/journey-of-wawel-treasures-to-canada.

Linda Batchelor – Volunteer NMMC Bartlett Library, February 2019.