We are fortunate in having a very full account of life ‘on board’ Diamond Rock in an account which appeared in two parts in the Tyne Mercury. The author remains unidentified in the publication. Whoever he was, Capt. Maurice clearly ranked him in the officer class, as he regularly shared his ‘table’ with our essayist. His apparent lack of Naval duties, seems to exclude any of the lieutenants.

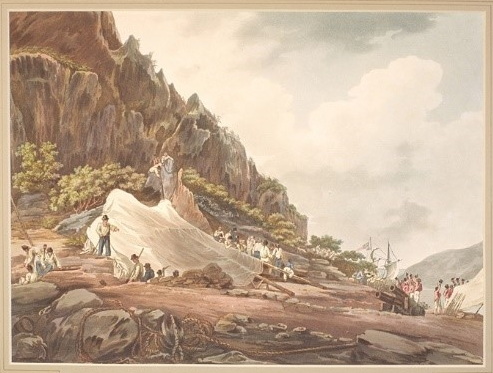

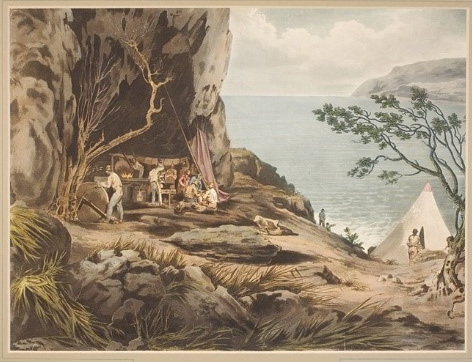

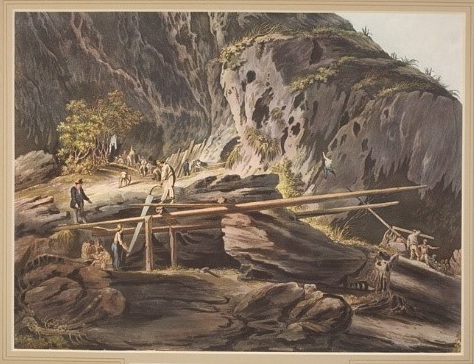

The author was almost certainly John Eckstein, who was for a time one of Centaur’s ships company. He was an accomplished artist who produced an impressive set of paintings of life on the rock, which was published in London during the first half of 1805.1

DIAMOND ROCK MARTINIQUE.

The following interesting Account is extracted from a Letter received in the Spring of the present year. Our Readers, we imagine, will be amused by the vivacity of its style, and the lively picture it contains of a Colony of British Seamen, settled on so singular a spot.

At present, my dear friend, take all your romantic ideas about Highgate, Hampstead, and the lower regions of Norwood Forest, or even your own Chalfont, and burn them, to make room for a set of new ones, as wild as those of Crusoe, and more true. There is in this hemisphere as island called Martinique, belonging to the French, as you well know; and there is near it, in the middle of the sea, a huge rock, called the Diamond, from its shape, I suppose, which very likely you do not know. This rock has stood since the creation, no doubt, without man, bold as he is, ever daring to venture near its destructive form. The surge has beaten against its spiky splinters for these thousand years, in vain anger, and the hollow cave still remurmurs to the howling winds. This mighty rock has been gazed at by all nations, but trodden by none; sea-crabs alone have ventured up into its holes, and birds of prey have alone ascended to its rugged summits. Behold the genius of the deep, the genius of British enterprize! It is not a month since all this was; but now the voice of song and labour resounds through every part of it; wigwams and thatchings, cots and hammocks, appear in every hole; the pot and kettle’s smoke ascends, and the light glimmers in the cavities where sea birds and bats formerly built their nests. Where was the boasted ingenuity of the French engineering? It was too tremendous for their skill. Now they stand on the shore with their spy-glasses, and wonder as the wiseacres did when Columbus gave the egg the might thump. Yet think not my dear friend, that I have conjured up the genius of fancy. More than I can say, and more than you can believe, has been accomplished by the fertile enterprize of Commodore Hood, and the indefatigable exertions of the Centaur alone. Believe me, I shall never take off my hat for anything less than a British seaman.

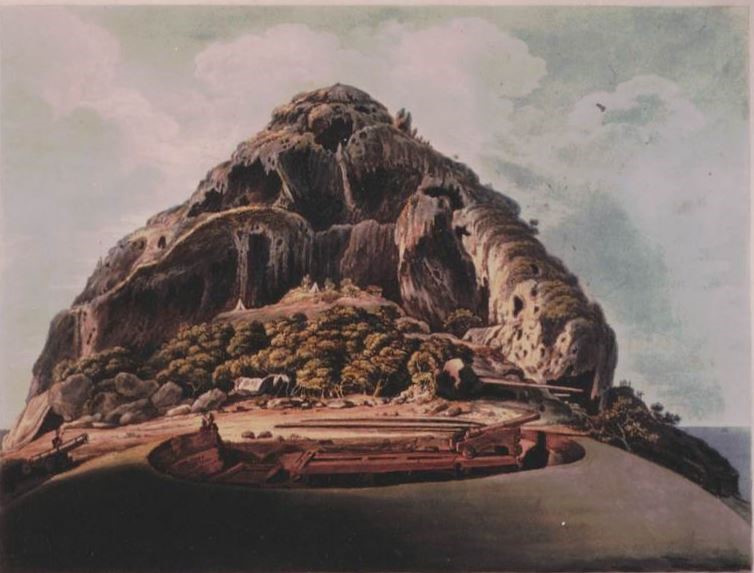

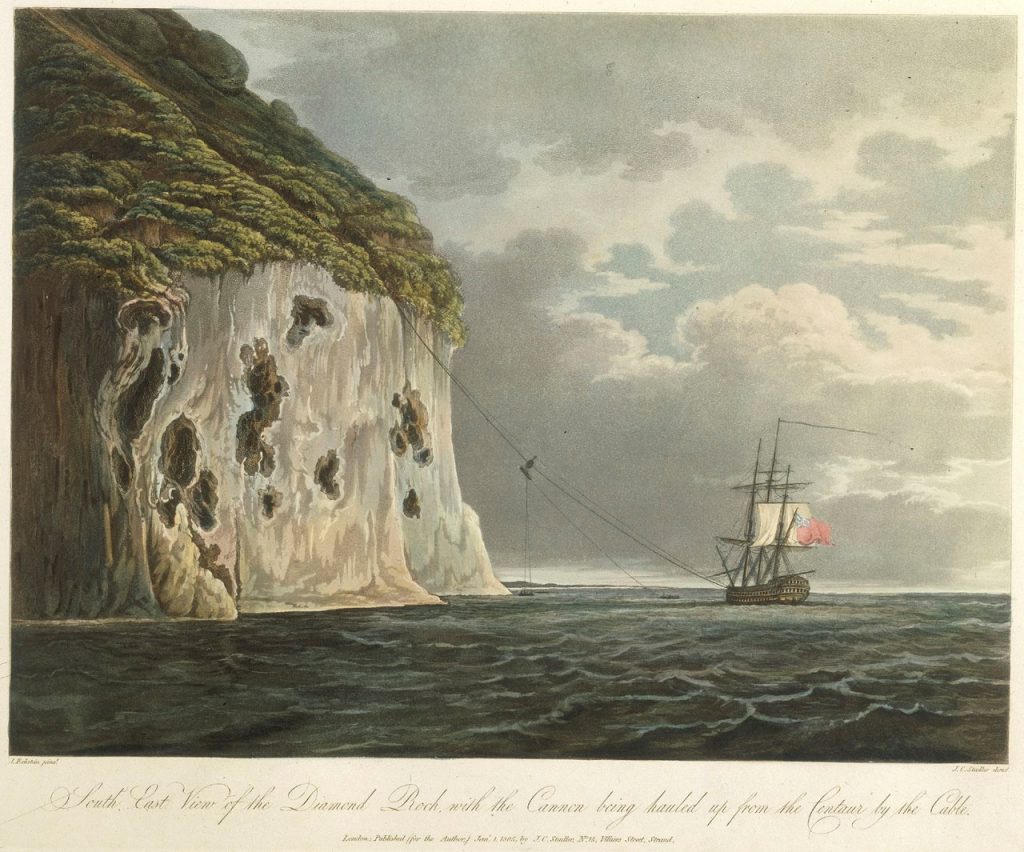

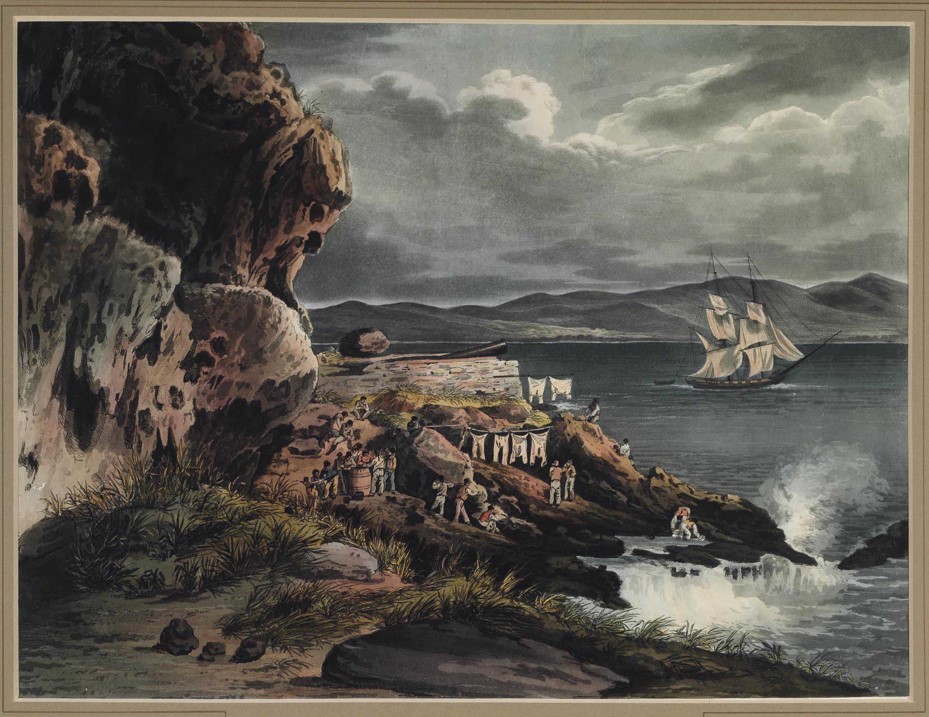

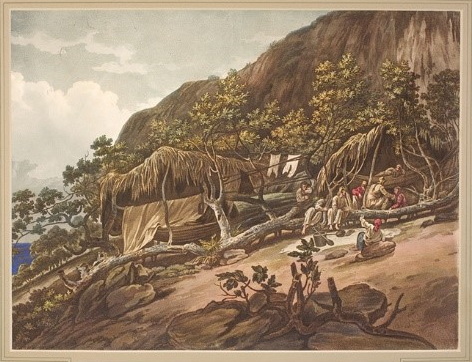

Were you to see how, along, a dire, and I had almost said, a perpendicular acclivity, the sailors are hanging in clusters, hauling up a four, and-twenty pounder by hawsers, you would wonder! They appear like mice, handing a little sausage; scarcely can we hear the Governor on the top, directing them with his trumpet, the Centaur lying close under it, like a cocoa-shell, to which the hawsers are fixed. From the ship, which you must know is a 74, issued forth carpenters, smiths, turners, miners, machines, engines, and directors, and also your friend, their humble historian, who thus attempts to describe their gigantic exploits, though his pencil is unable to keep pace with their labours. I have a thousand things to tell you about myself, but nothing can I think of relating, while a microscope would hardly discover do diminutive a being, stuck in some crevice of this tremendous piece of grotto work, which is itself scarcely a carbuncl on the nose of the West Indies. Here I have lived for a month, drawing from morning till night, free as a goat that browses on the rock, and happy as the broodings of fancy, and the goodness of every body around me, can make a mortal, in the elysiam of ideas, and the luxury of high feelings. Bt I will now endeavour at something more like method, lest you should conceive the heat, which is excessive, has disordered my brain more than it usually is. The height of the Diamond is 600 feet, measured by a quadrant on board of the Ulysses; its circumference is not quite a mile, Martinique being close by within three quarters of a mile. The south side of the rock is inaccessible, it being flat steep, like a wall, sloping a little upwards, and the grass climbing up. The east side is also inaccessible, with an overhanging cave about 300 yards high; on the south-west side also are caves of great magnitude, but perfectly impregnable from that side. The west has breakers running into the sea, where the people first landed; here a guard is placed, and a lodgement made for stores; the landing is sometimes very dangerous, and at best you must creep on your hands and knees, through crannies, till you wind to the north-west side, every moment endangering your neck, should you slip. At last you reach the north-west, and here a slope of green fig-trees, a beautiful grove, first relieved the eye; this grove mounts up, under an enormous grotto which overhangs it, and here is now the tent of the governor, Captain M. Close by stands the tent which I inhabit; our family consists of a Newfoundland dog, a cat and kitten, and such wild sparrows and rabbits as chuse to visit us.

The surge often drives the spray as high as I sit; it is a music of which the ear never tires. I mess with Capt. Morris [Maurice], and we generally have visitors; the link of good nature is never broken, and we are profusely liberal as our circumstances and situation will admit; each lends the other his spoon, a pen-knife serves to cut up a joint, and fingers are substitutes for forks. The language of the heart flows here as purely as at the proudest board of ticklish taste; it is unadulterated from the force of nature. A bottle of Madeira and Claret follows dinner, to the remembrance of our friends in England. Fish, melons, &c. are sometimes brought from the Martinique shores, by the small boats which venture from gain or curiosity. We throw the shot upon their shore, and bring every boat to if we please. In the evening we walk in the Queen’s battery, thus tracing our rocky path along the overhanging ridge, to the summit, where our little brotherly tents spread their canvas on cross sticks, and are baracadoed with stones. Warmed by the genial bowl, we shake hands, bid good-night, retire upon the dried grass, and, rolled in blankets, sleep shuts our weary eye-lids, while neither fear nor uneasiness intrudes or our repose. At night, the continual roaring of the sea below is only interrupted by the replies of watching sentinels above, or the screams of the tropic birds, who sweeps from the top of the water to catch fish, which he providently lays by his nest to feed on by day. If then, sometimes, the thought of those distant beings dear to affection, keep mu senses awake, I behold the starry face of the heavens as I lean on my elbow, the sea stretching before me her immeasurable blue domain, and, trusting to the wakeful eye of Providence, I sink in reflection – thought dissolves – and oblivion removes every trace from the tablet of memory.

There are some springs in the rock, but they are of a mineral nature, and occasion the gripes. Some tanks, however are building, and almost finished, which will in one day catch as much rain-water from the rock, as will serve the colony for half-a-year. This place is very healthy, notwithstanding which an hospital has been begun, and the walls are already mounting. I know not what the good people of England will think of so hazardous an undertaking, in a place where no spade can make an impression, and where every thing is blown and torn from it by mining; the lime fetched from St. Lucia – the bricks cut out with gunpowder – saws, hammers, anvils, &c. made out of old anchors – forges going – and all this within the short time of about six weeks: for my own part, I am astonished at the efforts of a single ship’s crew. But, however perilous of access, the sailors build like sea-birds, their nests in the most terrific caves. Like bust ants, the crew creep about the ride mass: every where they are at work; the saw, the anvil, the axe, the grating file, resound; mines explode, and the flying fragments rend the air.

[To be concluded in our next.]

Tyne Mercury, December 4th, 1804

DIAMOND ROCK MARTINIQUE.

(CONTINUED FROM OUR LAST.)

The seamen call their coming here going ashore; and so powerful is this liberty-looking wildness of nature to the mind, that they return to the ship with reluctance, though often while here, deprived of every comfort and allowance. Here they will work twice as hard, and conceal their being ill, and even die without help, rather than leave the barren rock to return on board. A few days ago the Centaur drifted, was driven out to sea, and we were left without water; but whatever I may have read of Roman heroism, I every day see more striking instances of that virtue among British seamen. Thirsty, and often without bread, in the heat of the sun, on this comfortless, and at present barren rock, in the face of the enemy, who is erecting his works to throw bombs, they remove rocks, colonize flinty soil without intermission and without murmurs, and can still generously share the little they have left. Here I have found, that the fine sayings of love of country, and the hearty wished of our native land, flow from the genuine warmth of the heart, and evaporate not like the effusions of the bottle, or the vaunting of plenty and a full belly. Here resolutions are formed in the face of want, and executed in despite of fate. The boats crew who cut out the Curieux from under the batteries of Forts Royal. Were true lives and fortunate men of his Majesty. When the marines are gone from the rock the other day, on an expedition, and in the middle of the night, the alarm was given, every man was in five minutes on the batteries to defend his Majesty’s rock. The expressions which, in the momentary expectation of danger, burst from the loyalty and courageous love of country from our sailors, would shame the brightest passage of admired Sophocles; and often would the death of an humble tar appear with greater lustre, than the laboured exit of a splendid monarch.

The manner of feeling which nature has given you is so different from the many, that I dare not write to you in the language which costs me no trouble in composing. I am now sitting on the top of the rock, and an old barrel is my desk, with no other library than a blank pocket-book that I bought at Falmouth, and in which I both write what I think, and draw what I see.

Were it not for the duties which I owe to my family, and for the strong affection which I bear them, I could stay on this rock all the days I have to live. It is to me one of those spots on earth which are truly desirable; it breathes all the independence of nature; it is large enough for the curious inquiry of all the year round, hey not too large to be grasped by the mind every moment, or to be actually over-run in a few hours; not far away from the rest of the world, it enjoys a everlasting spring, sheltered from the heat and rain, do that in the heaviest shower you may breakfast and dine in the open air; and behold the hurricane rage below and around, while you indulge in the gentle breeze. The habitable part, of which I have spoken, is like a horse-shoe, the favourite shape of popular theatres, covered with a canopy of rock. But what are all theatres to this? The Roma theatre is a child’s card-house to it! The morning dawn: the whole world waits as she draws the curtain; the air is still, the ocean blazes, and the actions of good men, unlacquered with the leaf-gold of fashion. An everlasting change of scenery is displayed: see the clouds encircling the tops of the mountains; now the sea, swept in showers, and curling with squalls; now the sun gilding the sugar-cane fields; the sublime of nature is here so quickly and so agreeably mixed with the beautiful, that the mind of man has not time to be satiated with objects. When you are on the top, you behold the wide world and the great ocean; the sublime fastens on the foul; creation can present nothing more grand. When you descend, the green land, where you may see the carriages travel, and count the feeding sheep, sweetly revived and beautifies the scene; nor had the trouble of descending subtracted from the pleasure. You have found an appetite, a cheerful spirit, and you glory in health and existence. So natural is the inborn love of the sublime, that could any inhabitant of the city pop his head out and behold so wide a field of nature, his soul would be instantly immerged in it, and he would forget all his little concerns; and so sweet is the change from it to the minute and beautiful, that after so trying a sight, you examine an insect or a flower with infinite pleasure, sinking into the calmness of relaxation.

Tyne Mercury, December 11th, 1804

The images contain a great amount of detail and show how the seaman had established a fully-functioning community, supporting both the batteries and the squadron.

John Eckstein’s book about life on the Rock was advertised:

THE DIAMOND ROCK, NEAR MARTINIQUE.

Speedily will be published, by Subscription, price 10l-.

A MOST ELEGANT WORK, on Whole Sheet Royal; containing fourteen highly-coloured Plates of VIEWS of the DIAMOND ROCK, near Martinique. One Plate or Portrait of the Officers of His Majesty’s Ship Centaur, &c. and an elegant Title Plate, with the Portrait of Commodore Sir Samuel Hood, K.B. &c. (to whom the Work is by permission dedicated), accompanied with a Topographical and Historical Account of the Rock, since taken possession of by the English. The Drawings have been made on the spot by Mr. J. Eckstien, (in His Majesty’s Service on that station), for whom the Work is to be Engraved, and Published by J. C. Stadler, 15, Villiers-street, Strand; where the Original Drawings, as also Specimens of the Prints may be seen, and where Subscriptions are received. The price to Non-subscribers will be considerably advanced.

Morning Post, Thursday, February 28th, 1805

- Eckstein, John (1750-1817). Picturesque Views of the Diamond Rock taken on the spot and dedicated to Sir Samuel Hood, K.B., Commodore and Commander in Chief of His Majesty’s Ships and Vessels employed in the Windward and Leeward Charibbee Islands. London: published for the author by J.C. Stadler, 1805.