Lieutenant Walter Benson Hunkin RN

18 September 2018I join the Royal Navy

2 October 2018 Early Recollections

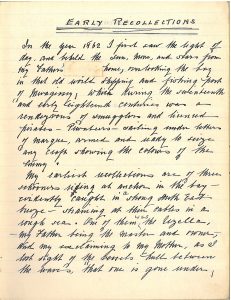

Early Recollections

In the year 1862 I first saw the light of day, and beheld the sun, moon, and stars from my father’s home overlooking the bay in that old world shipping and fishing port of Mevagissey, which during the seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries was a rendezvous of smugglers and licensed pirates – privateers – sailing under letters of marque, armed and ready to seize any craft showing the colours of the enemy.

My earliest recollections are of three schooners riding at anchor in the bay – evidently caught in a strong south east breeze – straining at their cables in a rough sea. One of them was the Uzella, my father being the master and owner, and my exclaiming to my mother as I lost sight of the vessel’s hull between the waves, “that one is gone under, that one is out of sight”.

My grandfather in 1806 at the age of twenty-three was taken by the press gang and introduced to service in the King’s ships of the Royal Navy, eventually obtaining his discharge by the payment of a ransom, his sister walking from Mevagissey to Plymouth with the money for this purpose. For some years following he gave his time to the more remunerative and venturesome occupation of privateering – encouraged by the government and appealing to the younger seaman. At a later period during the war with America in 1812 as ship’s master, this ship and crew were taken by the enemy.

My father, a hardy and fearless seaman, of the old wind jamming school, who made his first voyage with his father at the age of eleven, and his last voyage at seventy-one, stirred my boyish imagination as I listened to his stirring tales of the sea, of banian days, salt-horse and hard tack, scurvy and yellow fever, the common enemy of the old time sailor.

When guano was first discovered on the island of Ichaboe, by a ship’s captain making a casual landing on the island, and bringing home a cargo. The hue and cry of ‘guano for nothing’ very soon spread and ships innumerable were very soon running down their southing in quest of a cargo of this valuable manurial fertiliser, the deposit of sea birds from time immemorial. He was a young seaman in one of those ships.

At anchor near the island lay hundreds of craft of every description, all the crews keen on collecting a cargo. The men landed in the ship’s boats, provided with picks, shovels and bags, they would seek out a pitch, fill the bags and ferry off to the ships, slow and laborious work, to fill the ship’s hold, taking several months. Under the circumstances, there being no controlling authority, with hundreds of men hustling for the best site for bag-filling, there was frequent quarrelling and fighting, order being eventually restored by the arrival of one of His Majesty’s Ships.

Bleeding at the nose was a frequent occurrence among the men, probably due to the phosphorous and ammonia contained in the guano. Numerous egg shells, the contents dried to the size of a pea were found in the deposits.

One of the crew having died, the master decided to take the body to the mainland for burial, and accompanied by the crew from another ship, they set out for the shore. In attempting to land on a beach, the boat capsized, throwing men and corpse into the sea. Their mission was, however, in due course accomplished and their dead shipmate laid to rest on the inhospitable shores of South Africa.

As a seaman in a ship waiting cargo at a South American port, yellow fever prevalent, sailors dying like flies, and the black flag hoisted daily for the undertakers boat to come alongside. All the crew in their ship were laid down with the exception of the boy. The boy nobly did his best to carry out the doctor’s orders, attending to the wants of each one, as necessary, in his endeavour to nurse his shipmates back to health. Fortunately all but one man recovered. Even to his old age my father always had a feeling of thanks and friendly respect for this boy shipmate, whom he always declared nursed him back to health. I am sure in later days they must have often recalled that eventful voyage.

On a voyage when traversing the southern seas, and having to fall back on the reserve water casks in the hold, it was discovered that all the water was putrid, but it was drink that or die of thirst; even after being boiled the smell was so foul that a sup could only be taken by pinching the nose. This continued for three weeks, when a tropical shower renewed the water supply. And yet there were no ill effects on the health of the crew.

At a later period when Master of the Minion of Liverpool, the owners had fixed the ship for the Canary Islands to bring home a cargo of fruit, and to load in an open roadstead. An altercation arose with the superintendent as to the amount of ballast required for the safety of the vessel, if it became necessary to leave the roadstead. The superintendent refusing to comply with his request, he declined to take the ship to sea, consequently he lost his employment. What he foresaw might happen did happen. The Minion had to leave the anchorage in an approaching storm and being under-ballasted she never returned.

The call of the sea is in my blood in as much that I am descended from a stock with a long seafaring record and an ancient Cornish pedigree. It is recorded of one William Hunkyn of Liskeard from whom we trace our descent, as being mentioned in a deed conveying to him a grant of land bearing date 27 Henry the VI 1449. A descendent, John Hunkin of Liskeard and South Kimber, mentioned in Vivian’s Cornish pedigrees and in the history of Liskeard was appointed under a charter of Elizabeth to be the first mayor of Liskeard.

With the coming of the Commonwealth and the civil communions, his son John Hunkin of Gatherley, who married Jane, second daughter of John Canrock, Lord of the Manors of Treworgy, Harwood, Woodhill and Liskeard and his family took sides with the Parliament; one son, Major Joseph Hunkin becoming Governor of the Isles of Scilly. After the Restoration they, like many others, paid the penalty and were stripped of their honours and their possessions. Down through the generations this family has produced several men of courage and grit who have made good and shown themselves worthy of responsibility and leadership.

Not so many decades have passed since the latter was vividly demonstrated, when one of our kin standing on the quarter deck, threatened by a mutinous crew, fearing not to play the part of judge, jury on the other man, he declared the first man passing the mainmast would pay the penalty. Being put to the test, he kept his word, and was exonerated.

Boyhood

At an early age I commenced my education at a dame’s school. I can only remember the names of two boys who attended this school at the same time. After a time when we had been taught to read, the three of us day after day read the fourth chapter of St Mark until we could repeat the forty-two verses off by heart.

Having outgrown the dame’s school I was transferred to the church school. The master was a very good teacher of elementary subjects and had no scruples about the use of the cane. For offences real or imaginary he laid it on freely, on all alike. On two occasions, when flogging a boy with a heavy cane, the boy jumping over the desks, the master following him and punishing him to such an extent, he made us quake with fear. Consequently my parents moved me to another school kept by a man who had been obliged to give up his business in London on account of ill health.

At this age my mischievous boyish spirit commenced to show itself, both in the school as well as outside. Frequently I found myself falling into trouble, often through the prompting of others less spirited and venturesome than myself. The master’s patience very soon became exhausted; he could tolerate me no longer. My exuberant spirit was too much for him, with the result that I was expelled, a humiliation indeed for me and an annoyance to my mother.

My next educational establishment was conducted by a retired shipmaster, Capt. William Ball. The Captain was very good at mathematics, well versed in history and geography. In addition to the usual school subjects, he taught navigation to those launching out on a nautical career. Numerous men have looked back with pride, and thanked the old Captain for starting them on an educational foundation on which they built successfully.

After some little misbehaviour on my part I was allotted a seat close to the Captain. There, I was compelled to pay more attention to my books. From the windows there was a good view of the harbour and the bay, and the Captain never losing his interest in ships and sailors would frequently lower the window and, through his old fashioned long telescope, sight a ship passing or coming to an anchor. Often calling out the name of the vessel: “that is the Sunflower bound from Leghorn to London”, the Freedom, the Roseland, or any of the local owned craft all readily recognised by the Captain.

The Captain was an indifferent writer, my own writing not being any good. One day when sitting by his side he said to me: “Walter do you see that telescope? That belonged to my schoolmaster, a retired sailing master – navigator – from the Royal Navy, who fought at Trafalgar and after the battle, when writing home, mentioned that he had been wounded but it was not on the right side, the front side or the left side.’ He made me a present of that telescope for being the best scholar in the school, with the exception of writing, remarking ‘that writing was only an imitation and a monkey could imitate’.

At the age of fourteen my school days were over but my education by no means finished. In my home town there was not much to choose from by way of a career. There were fishing boats, an apprentice to one of the small tradesmen, or the sea. My brother after leaving school had gone to sea with father. But my father, who always declared that a sailor’s life was a dog’s life, was rather inclined that I should learn a trade. The sea had the stronger call for me. While waiting for my father’s return, instead of idling my time, in the spring of 1877 I made one of the crew of a mackerel drifter, the English, the skipper being also the owner. At first I was very sea sick and one of the older men, Shadrick by name, helped me in many ways, his kindness I always remembered.

In the month of June the skipper decided to try his fortune by fishing for mackerel from the port of Newlyn. The first night of fishing from that port was attended with such unheard of success that it is spoken of in Mevagissey to this day. Probably the skipper had never been to the eastward of Start Point, or westward of the Lizard before, so this venture to the western port of Newlyn was to him almost on a par with the voyage of Christopher Columbus sailing forth into the unknown.

On leaving Newlyn for the fishing grounds for the first and only time, we sailed along the coast in the direction of Land’s End, eventually at the sunset hour, the time of casting out the nets; the boat was a few miles to the westward of the Longships. I am certain there was not a man in the boat who had the least idea of the tides and currents at this spot.

Overboard were shot the nets, and the usual time given for the mackerel, if any, to enter the mesh. In due course, as customary, the end of the net was hauled up to ascertain if there were any indications of fish and to the astonishment of all hands it was found that a quantity of herrings had been netted. After an hour or so it was decided to haul the nets and to the skipper’s great joy they were full of fine fat herrings, as much as the boat could carry. Such a catch of herrings at this spot and at this time of the year had never been known before. This remarkable catch was spoken of by Mevagissey fishermen fifty years after. At daybreak two well-known rocks were sighted, and I remember the skipper saying he knew it was the Brisons as he had seen a picture of these rocks in a paper showing the loss of a ship with all hands except the captain’s wife and a Negro who had helped her on to the rock.

A course was set for the Land’s End, eventually passing inside the Longships and so on to Newlyn; there being very little wind. the boat did not arrive at Newlyn until ten pm. The fish were auctioned and sold for sixteen shillings per hundred, but the buyer, when he came to pay up, would only pay eight shillings, as he said the fish were broken. At that price it was a good night’s work. The boat remained at Penzance for a few days, the skipper not daring to risk his gear in these unknown waters again. He had made a good week’s work and decided to return to the home port, thus ended this eventful and historic voyage.

A week or two later I joined another fishing boat, the Bessie, skipper Richard Pomeroy, a man that I always respected for his kind manner and encouraging words to me. Many years after, when I had reached officer rank, skipper Pomeroy was apt and I think proud to say “that is one of the boys I helped to train”.

Early in July the boat set sail on a voyage to Whitby for the North Sea summer fishing, I little thinking what the North Sea fisheries held in store for me at a later period in life. The voyage was completed in pleasant summer weather and fishing from the port of Whitby commenced in due course attended with fair success.

The work proved very harsh, especially when landing the fish on the beach, and off to sea again immediately after, with consequently much broken rest for all hands. After being there for about two months, one night the nets became so heavily laden with herrings that they could not be got on board, the line parted and the whole train of nets were lost.

On the day of leaving Whitby in the empty boat for our home port, I remember the men saying that was enough of the North Sea for them. Silently in my own mind I determined that the North Sea nor any other sea would be visited by me again in a fishing boat; in fact that I had no intention of becoming a fisherman.

In October I joined the schooner Gitana of Mevagissey at thirty shillings per month. A cargo of china clay was loaded at Charlestown for Dunkirk. In Dunkirk docks no ship was allowed to have a fire on board without permission when a watchman was placed on board and whose expenses had to be borne by the ship. Consequently nearly all the cooking from ships in the docks was done on shore in cook-houses provided for the purpose. It was my job to take the food to and from the cook-house.

The man in charge would make a note of the name of the ship and attend to the cooking. It was a strange experience for me, seeing that these were rough and hardy sea dogs jabbering in every language but one’s own, each getting excited over their own pots, containing every conceivable delicacy according to the nationality. Sometimes when the cook in charge had failed to do his job well, there would arise heated words. The men from the ships with their sheath knives in their belts, wild and fearless looking fellows, Italians, Greeks, Negros, Scandinavians etc., made me feel very small and frightened.

The old cook appeared to speak any and every language, and would say “what ship boy?” Giving him the name, he would produce the dinner all steaming hot to take on board. There was the climbing over other ships with a boiling kettle or pot, the right of way disputed by a ship’s dog. This was anything but fun for me, although the kind-hearted sailors, British or foreign, would always be ready with a helping hand. I was not sorry when we pulled out of Dunkirk dock. There being no cargo available, the captain decided to return home in ballast. On the voyage the ship took shelter in Portland and remained two weeks weather-bound.

The Captain, who was fond of a glass of beer, would take me in the boat with him, row ashore, go into a pub and leave me to mind the boat awaiting his return. That was anything but a pleasure to me.

Eventually with a fair wind, sails were set for the voyage to Falmouth where, on arrival, the ship was moored for the winter and the crew paid off. No time was lost in making my way home.

I am still undecided as to what my career is to be. I am inclined toward the sea. Two of my school mates just about my own age going to sea with their fathers for the first voyage never returned, the ships being lost with all hands.

In February ‘78 my father, now being at home, it was arranged that I should become an apprentice to Mr William Body, a house carpenter. I went to work with a good will doing odd jobs and working with the older apprentices. The senior apprentice was a fine helpful young fellow but the second apprentice was very fond of ordering the master’s son Charles – about my own age – and myself to perform any job that he did not like himself.

The master having orders to carry out certain repairs to some old property, taking this apprentice with him, set out to examine these old houses and make the repairs necessary. They soon discovered that although the human element had departed they left behind quite a number of inoffensive wingless insects. These, no doubt thirsting for blood, made a dead set on the master and his assistant, from which assault they were compelled to beat a hasty retreat, accompanied by unlimited numbers of the attacking army. Charles and I had the laughing side on that occasion. After a few months I found that so many dirty disagreeable jobs fell to my lot that I became discontented.

My apprenticeship was to continue for six years, and the question that arose in my mind was, what then? Answer – London, America, or Australia. If I have to leave Mevagissey to earn a living, why not go at once?

The urge of the sea is still with me. In September Mr Body was doing the woodwork of new fish stores opposite the King’s Arms public house. These stores were to have a flat roof – an idea worked out by the owner which proved a failure – of wood boarding, coated with a composition of pitch, tar, sand and cement, the apprentices doing the work. This dirty labourer’s work thoroughly disgusted me, but while the master’s son was helping I had no room for complaint.

One morning Mr Body and myself only appeared on the scene, and when ordered to commence work, I politely asked who was to lay on the pitch and tar? The master answered, you and me, to which I replied, not me, whereon he said I had better go. I promptly took him at his word, put on my coat and departed. My father at the time being on a deep water voyage, my mother concluded that I was quite unmanageable.

My career is again in the balance, I must come to a final decision for myself. The call of the sea is strong; shall it be the Royal Navy or the Merchant Service? My forefathers for generations had been merchant sailors and ship masters and yet they had to continue it for long years. Why not break the chain of tradition and enter the Royal Navy?