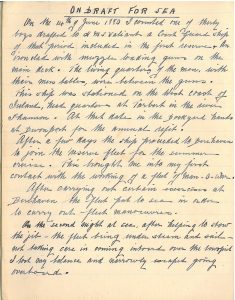

On the 14th of June 1880 I counted one of thirty boys drafted to HMS Valiant, a coast guard ship of that period, included in the first reserve; an ironclad with muzzle loading guns on the main deck.[*] The living quarters of the men, with their mess tables, were between the guns. This ship was stationed on the west coast of Ireland, headquarters at Tarbert in the River Shannon, at that date in the dockyard hands at Devonport for the annual refit. After a few days the ship proceeded to Berehaven to join the reserve fleet for the summer cruise. This brought me into my first contact with the working of a fleet of man-o-war. After carrying out certain exercises at Berehaven the fleet put to sea in order to carry out fleet manoeuvres.

On the 14th of June 1880 I counted one of thirty boys drafted to HMS Valiant, a coast guard ship of that period, included in the first reserve; an ironclad with muzzle loading guns on the main deck.[*] The living quarters of the men, with their mess tables, were between the guns. This ship was stationed on the west coast of Ireland, headquarters at Tarbert in the River Shannon, at that date in the dockyard hands at Devonport for the annual refit. After a few days the ship proceeded to Berehaven to join the reserve fleet for the summer cruise. This brought me into my first contact with the working of a fleet of man-o-war. After carrying out certain exercises at Berehaven the fleet put to sea in order to carry out fleet manoeuvres.

On the second night at sea, after helping to stow the jib – the fleet being under steam and sail – not taking care in coming inboard over the bowsprit, I lost my balance and narrowly escaped going overboard.

On the day following I witnessed for the first and only time a burial at sea, that of an able seaman who had died on board.

At the expiration of the summer cruise the ships disbursed to their several ports, the Valiant to Tarbert in the River Shannon where moorings were taken up for the winter.

One Friday when the usual weekly general gunnery exercise was being carried out the fire bell rang, whereon the guns were secured and everyone rushed to their fire station. At first it was taken to be exercise. When the word was passed: “fire in the magazine”, it sent a thrill along the decks that made everyone move. The pumps were rigged and hoses got along in double quick time.

The magazine being open as a part of the gunnery drill something had taken fire there. The captain of the forecastle, his station being at the scene of the fire, on arriving at the magazine entrance saw the smoke arising through the hatch. The men stationed in the handing room having come up. He immediately rushed down the ladder, entered the magazine, followed by the commander. Promptly seizing the wooden magazine curtains and blankets, they succeeded in smothering the fire and bringing it under control. It was a nasty few minutes for all hands and a relief to hear the word passed that the fire had been caught in time, the captain of the forecastle being highly commended for his prompt action.

At this time the Land League agitation, the ‘pay no rent’ cry, was at its height in Ireland, with many evictions and prosecutions, a few gunboats being employed in taking the Irish Constabulary from place to place to the scenes of some of the evictions.

On account of the trouble in Ireland it was decided by the government that the crews of the coast guard ships stationed in Ireland being only half manned during the winter, should now be brought up to the full complement. A large draft of petty officers and men arrived from the receiving ship at Devonport.

On the 18th of November, my eighteenth birthday, in accordance with the King’s regulations, I was advanced to a man’s rating of ordinary seaman, with a wage of 1/3d per day.[*]

With the closing days of 1880, and the approach of Xmas, fourteen days leave was granted to the crew one watch at a time. The distance and cost to get home was too much. I had to remain on board and make the best of it.

1881

The early months of 1881 proved to be very severe with frost and snow and, as there was nothing in the way of a fire or other means of warming the men’s quarters, there was not much comfort for anyone.

In the matter of messing and cooking in this class of ship, there were about twenty-five men in each broad side mess. Each day one of the men acted as cook of the mess and held responsible for the preparation of the dinner, taking it to the galley, fetching the bread, the breakfast cocoa, dinners, rum and tea at the meal houses and keeping the mess and mess traps clean etc.

The ship cook had his work cut out to cook for all hands. The cooking gallery had two ovens and two coppers, in which coppers the salt beef or pork, pea soup, vegetables, cocoa, water for the tea (brewed in the copper) and sugar added ready for drawing off into the mess kettles, was all done. The preparation of the food and class of cooking can be imagined, under such conditions.

The rations for each man per day were 1 lb of beef or pork, 1¼ lbs of biscuit, of soft bread 1 ½ lbs, ¾ lb of vegetables if obtainable, 1 oz. of cocoa, ¼ oz. of tea, 2 oz. of sugar. If a part of the meat or bread was left behind, four pence per lb for beef and three halfpence per lb for bread was allowed in lieu thereof. This, with a contribution from each man, would go to buy flour, potatoes etc. According to the regulations there was always one salt provisions day per week, even in harbour, where fresh meat was obtainable.

In the small town of Tarbert there was no room or attraction for the men to spend much time on shore. The only doors open to them were the licenced houses, with their vile whiskey and Irish Porter. There was not much amusement on board and the long winter evenings hung heavily.