The Guns of Prussia’s Cove1 or the Carters’ Battery

The late C18 was a turbulent time. Bays and anchorages on the coast of England, remote from central government and naval bases, were the haunts of enemy privateers. Mount’s Bay was one such bay, with a history of coastal raids by pirates and enemy raiders. These coastal communities were all clamouring for some form of protection – especially wherever sea-born trade was concerned. As hostilities with the American Colonies, and then Revolutionary France, ran on, Governments of the day approved and equipped a number of small, coastal batteries to placate the populace. Many of these were manned by Volunteer Companies of Militia, and later by members of the Sea Fencibles.

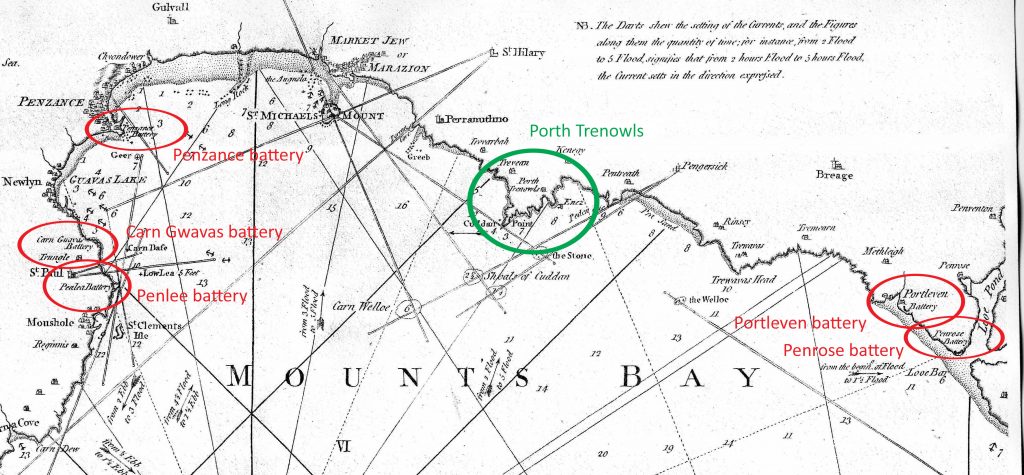

In this belligerent period there were a number of recognised coastal batteries located around the head of Mount’s Bay.

The 1794 chart shows five coastal batteries, that were officially sanctioned and in part armed by central government:

- Penlea (or Penlee) Battery near Mousehole

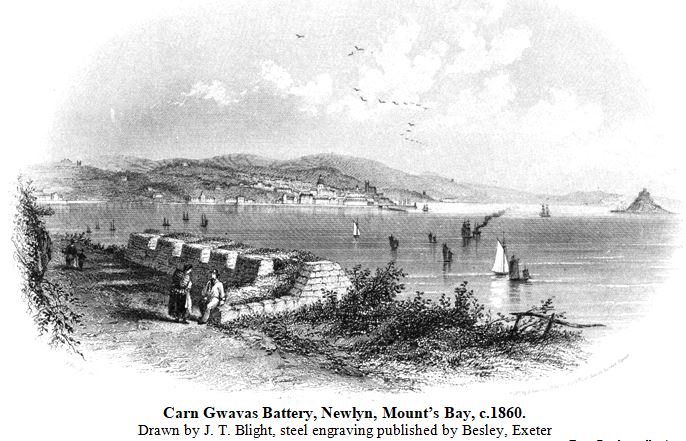

- Carn Guavas (or Gwavas) between Mousehole and Newlyn

- Penzance Battery on the rocky headland outside the harbour

- Portleven (or Porthleven) Battery, guarding that fishing porth, or cove – no harbour existing at that time

- Penrose Battery, guarding the mouth of Looe Pool, the Penrose estate, and in some measure Helston

Of the five batteries shown the Penrose Battery is the nearest to what might be described as a private battery. As well as protecting the approaches to Penrose House, it defended the soft underbelly of Looe Pool, leading directly up to Helston.

Intriguingly, given the primary dedication, none of these charts show the St. Aubyn’s battery on St. Michael’s Mount, or the small batter on Point Spaniard, between Lamorna Cove and Mousehole. Less surprising is that there is no indication of Carters’ battery at Porth Trenowls. So far as we know the St. Aubyn’s battery on the Mount, was privately funded, but it also guarded the town of Marazion, so this battery’s apparent lack of official recognition on the charts is a little puzzling – especially as the original version of the chart was dedicated to Sir John St. Aubyn. That the ‘Mount’ battery was officially recognised in this era is borne out by its featuring in some detail in a report on the Coastal Batteries, submitted to the War Office, by ‘Captain Parley, Com.dr Rl Engineers &c &c.,’ in January 1812.2

Carters’ Battery was of course, something else again – as may have been the one on Point Spaniard.

The Carters’ fiefdom, was commonly known as Prussia’s Cove, with all its implications of personal possession, though the family were merely leasehold tenants. Lying just within the parish of St. Hilary, tight with its border with the parish of Breage, Prussia’s Cove, was just one of the names ascribed to this cove, and somewhere within its bounds in the latter half of the C18th a small battery of ‘defensive,’ small-bore cannon was erected by the Carter brothers.

[Courtesy of HM Hydrographic Office, Taunton]

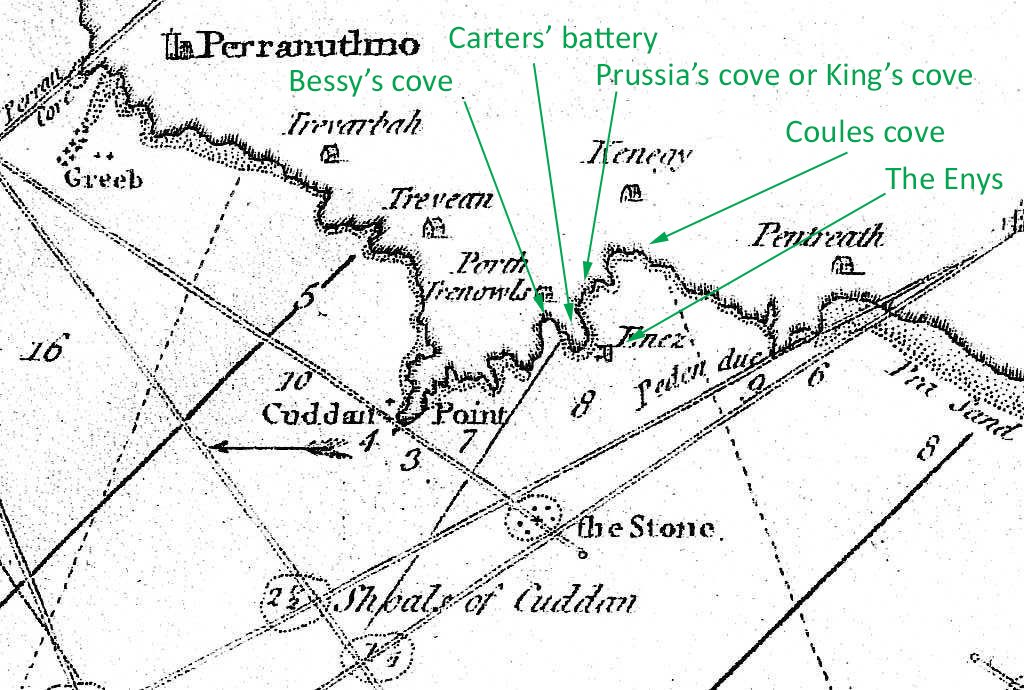

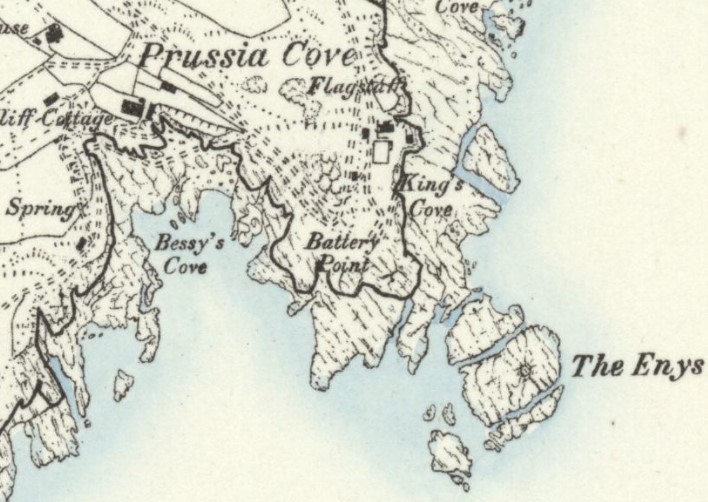

We can be fairly precise about the actual position of Carter’s Battery as the 1877 OS map marks ‘Battery Point’.

This small headland overlooks the narrow channel of water running between King’s Cove and a reef of rocks known as the Enys (otherwise Enez or Enis), with Bessy’s Cove to the west. Here, it would have been hidden from close scrutiny by the Customs officers in Penzance, with their ‘long-glasses, by the bulk of Cudden Point.

We cannot be precise about the location of the battery on the ground because the headland has been reconfigured in the intervening two centuries. The lane leading to the coves has been widened and re-aligned, obliterating all traces of the battery, and walls have been built. However, it is possible to make out some low dry-stone walls (just under the bushes by the wall in the picture above) which appear to have been put in place to create a level platform.

In the period when the battery existed the immediate area about it was loosely known by the name of the farmstead lying in a vale a few hundred yards inland of the headland: Trenowles. On either side of the small headland where the battery stood are several small rock-bound coves – Bessy’s (otherwise Bessey’s, Betsey’s, Bessie’s or Betsy’s cove), under the south-westward face; King’s Cove – on the south eastern side, right under John Carter’s house; and Coules’ Cove – a little further round to the north eastward. Each served in the running of contraband goods, depending on the prevailing weather conditions.

(Courtesy of Penlee House)

The chart clearly shows the area adjacent to where Carters’ battery stood, under the name Porth Trenowls. This was not a hard and fast name, and even the Custom House officers at Penzance, within which port’s jurisdiction it lay, could not agree on a set name – using Prussia’s Cove at times, Carter’s Cove on occasion, Porth Knowles on others, or even Porth Enals. While one officer obliquely named the location as ‘Carters Terclores’, the meaning of second word being lost in antiquity. So, quoting from different contemporary sources, confusion can easily arise as to where precisely they were writing about.

The reason why Carters’ battery was erected is simple enough to answer. It served the same basic defensive function as the other coastal batteries in the vicinity, The cove was isolated. Out of sight from the main centres of population in Mount’s Bay, and difficult to approach overland. So this little coastal community was left very much to its own devices during this turbulent period of our history, when there was a real fear of invasion, or at least of seaborne raids. Privateering was actively encouraged throughout this period and small calibre cannon were readily available: so a little private battery was a common sense defensive precaution for those who could afford one.

The very isolated nature of the coves, situated close to a major mining area of Kennegie, made it a convenient centre for illicit trade. This was long before any concept of teetotalism gained a foot-hold in Cornwall and cheap alcohol found a ready sale amongst truculent miners –‘The Tinners.’ Paying taxes was abhorrent and the free-trade importation of foreign spirits, tobacco and other commodities, was wholeheartedly supported. Taking advantage of this situation and trade potential, the activities of the Carter Brothers during the second half of the eighteenth century turned the cove into a significant smuggling entrepot – and, what actually went on there at the time was kept a pretty good secret from the authorities. Rumours abounded, but hard facts were lacking. Even then, however, when the balance of British justice was heavily loaded in favour of the authorities, the officers of the Crown still needed factual ‘information’ before they could legitimately take any action. Suspicion alone was not enough. Nearly every prosecution was based on a sworn ‘information.’

From the mid 1760s the Carter Brothers had established a flourishing smuggling trade. Importing some contraband goods for their own use but often running cargoes for other ‘merchants,’ carrying the contraband goods ‘on freight’. Cheap continental gin (Geneva) and brandy were their stock in trade but anything carrying heavy duty was handled from time to time, including that innocuous daily necessity of life ‘salt.’

While there was a code of honour among the ‘gentlemen of the coast’, living in splendid isolation, the brothers had to look out for themselves. No doubt intimidation played its part in keeping their neighbours cooperative and dumb: in this era all too often ‘might was right’. For several decades the Carters’ loose association with various Irish and Dunkirk pirates, privateers, and fellow smugglers, meant that they took all necessary precautions to defend their fiefdom – including the erection of their defensive battery of small cannon – four or six pounders.

Tradition has it that the battery was set up during the American Revolution, when the Carters outfitted several of their smuggling craft as privateers. In equipping their privateers the brothers had ready access to small-bore cannon, supplies of which were then widely advertised in the press:

BRASS CANNON are made at T. PYKE’s FOUNDRY in Bridgewater, Somerset, upon a new and improved construction, and of a new composition, which stands the Woolwich or Government proof. Merchants and Captains of privateers may be supplied on the shortest notice.

These guns are mounted upon swivel stocks, sliding carriages, or wheel carriages, like the common guns, now much used on board his Majesty’s ships of war; and by means of a semicircular solid piece of brass, working on a spring, are pointed and fired at any object with ten times the ease, expedition, and exactness, of any other guns now in use.

Fourteen ounces of the best sort of cannon powder is a proper load for a six-pounder on the above construction, and will throw a ball, and hit a mark, near two miles; the four-pounder requires ten ounces, and carries one mile and three quarters; the two-pounders six ounces, and carries upwards of one mile; swivels in proportion.

The small quantities of powder used in these guns, and their intrinsick value, when out of use, as old brass, makes them come to the purchaser cheaper than the common cast-iron guns.

Powder, ball, grape, canister, bar, and chain shot of all sorts, musquets with or without bayonets, swords, cutlases, blunder-busses, pistols, powder horns, speaking trumpets, pole-axes, pikes, cartridge and cartouch-boxes, flints, cartridge-paper, spy-glasses, night-glasses, watch and half watch glasses, compasses, benicall lamps, colours, drums, fighting and other lanthorns, ship stoves, ship bells, and ship kettles, with a large variety of other ship stores.

Sherborne Mercury, February 5th, 1781.

Competent crew who could serve them were readily at hand – many of them Royal Navy trained! There was no concept of continuous service in the Royal Navy of this era and hands were discharged whenever ships were de-commissioned.

Amongst the vessels that the Carters’ owned at this time was a new 197 ton cutter, called Swallow, built at Bridport in 1776-7. A regularly licenced privateer, she was commanded by Harry Carter, and nominally manned by a crew of 60. Mounting 16 guns, the Swallow had been granted letters of marque against the Rebel Subjects in America on April 3rd 1777.3 Towards the end of the year, on November 29th, the Penzance Customs officers complained to the Board of an audacious act carried out immediately off the town:

…on this Coast Yesterday afternoon was drove in this Bay and taken off the Prince Ernest Shallop Capt.n Jane Employed in the service of your Hon.rs at the Port of St Ives By a large Smuggling Cutter of 200 Tons Burthen having 14 Carriage Guns Mounted besides Swivels with 50 or 60 Men, On the above Cutter Coming up with the Shallop / which she Did at the Distance of about 100 yards or [so] from the Quay head in this Town, A man from on board said Cutter Hail’d Capt.n Jane and ordered him to hawl up his Boat and Come on board of him or he would immediately sink him, which was comply’d with, …

Punctuation was not their strong point, and while the officers don’t identify the offending cutter it could easily have been Harry Carter’s Swallow. The Customs shallop Prince Ernest, was technically attached to the St. Ives collectorship being the personal property of John Knill, the St . Ives Collector of Customs. We hear nothing more of her, but in August 1778 her ex-commander, Henry Jane, took command of John Knill’s privateer cum revenue cutter Brilliant4 which may well have been the re-named Prince Ernest.

While the reason why the battery was set up seems reasonably clear, what is not clear is why it was permitted to remain in existence for about fifteen years given that it was a constant thorn in the flesh of HM Customs and HM Excise. This remains a mystery.

The battery appears in official records several times over the period 1781-1794 and we have divided these accounts up into five chapters. The most dramatic of these is the raid on the Cove of 1792 when the Excise finally resolved to deal with the battery and its owners.