PZ.528 Boy Fred

4 May 2020PZ.614 Annie Jane

18 June 2020Nearly home when disaster struck – An account of the loss of the Lugger Jane ~ 26.PZ1

Re-worked a little more recently, this account was first published in the Western Morning News of Friday, October 10th 1980. In it Tony Pawlyn recalls a milestone event in the history of Mousehole and the fishermen of Mount’s Bay.

Over a hundred and forty years ago there was an event which, in the close fishing community of Mousehole, became a landmark in time for many generations. In 1880, luggers from the Mount’s Bay fishing ports – Newlyn, Mousehole, Porthleven and Penzance – had once again joined boats from all round the British Isles in the late summer North Sea herring fishery. Only the bay’s premier boats took part in this distant search for herring – which lasted between six and eight weeks. The luggers would reach the North Sea around the beginning of August. Some went up channel direct to the Yorkshire coast while others went West about – trying the Irish and Manx waters on their way. If they fell in with good catches some would remain in western waters. The majority, however, would work their way up the Irish Sea to the Clyde, crossing over to the East coast through the Bowline Canal, to fish out of Eyemouth, Scarborough and Whitby.

(Leon Pezzack collection, photographer unknown)

Very similar in all respects to the Edwin, the Mousehole lugger Arethusa ~ 65.PZ, made this voyage in 1863 [when she too would have had a PE., number]. Her owner/skipper James F. Ladner, kept a notebook which provides a typically terse account of such a journey. –

“June 20, 1863, left home for Ireland, arrived to Howth June 22 after a very fine passage over. We shot three nights since we have been over, caught 12 pounds worth.”

Abstracts from James Ladner’s pocket book, lent to the author by Owen Ladner in the 1970s

On August 11 the Arethusa left Howth and set sail for Grangemouth. In the North Sea some of the boats would go as far North as Aberdeen, but most of them worked off the Northumberland and Yorkshire coasts, following the herring shoals southwards as the season advanced. The Arethusa’s account continues:

“September 5 in Whitby. Caught eight pounds worth, some caught 30 and others no more than we. The time is going away, oh the failures of the fishery!”

“September 20, in Hartlepool, went there with 10,000 herrings did not make but ten shillings per 1,000. Throughout the week we caught about 50,000, made £3 of them.”

Although the 1863 season had not been up to James Ladner’s expectations, it was still better than average.

The 1880 season too was one of mixed blessings, as indeed were most, truth be known. Fishing as always was a bit of a gamble. When the fish were hard to find prices were high, but when the fishing was good prices would plummet, falling away to next to nothing. In the early weeks of August 1880, the herring catches were fair but the average price was low, sometimes as low as 1d. a hundred.2 During the September there had been some 300 boats working out of Whitby, the favourite resort of the Bay’s boats. But by the end of the month most of the Mount’s Bay boats were heading for home.

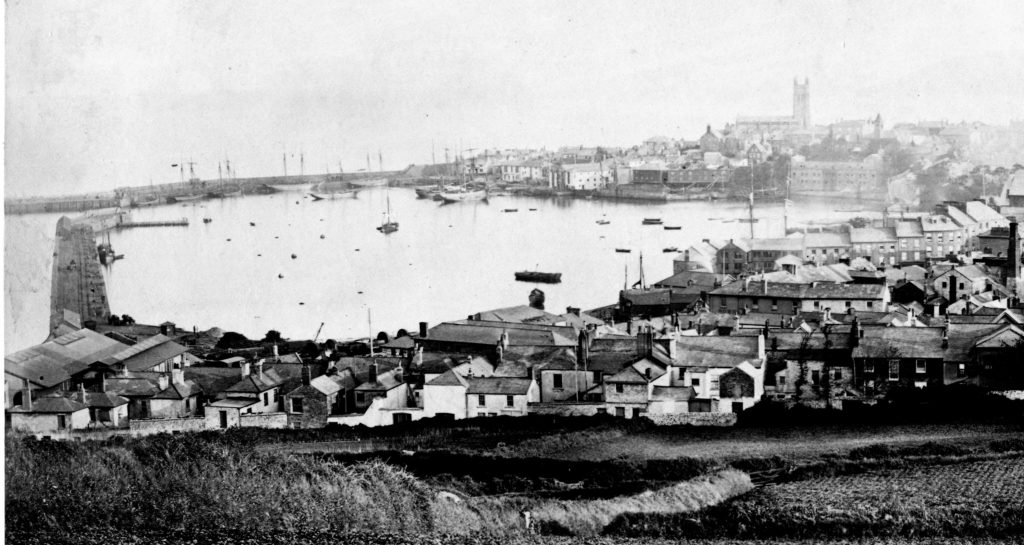

On the night of October 6th a strong gale from the SSW caught many of the Bay’s luggers in the Channel on the last leg of their passage home. Some put in for shelter at Dover, Isle of Wight and Plymouth, but those nearer home pressed on. In the false dawn of October 7th, four luggers, having rounded the Lizard, were being driven up the Bay by relentless seas. All were headed for the harbour at Penzance, as the baulks were down at Mousehole and only the old medieval quay then existed at Newlyn, where the summer mooring place, ‘Lodgia,’ was open to the South and South East.

But Penzance, an unnatural harbour at the best of times, was the only refuge there was.

First to appear in the gloom off Penzance pier head was the Percy~30.PZ. Within 100 yards of safety she was struck by a breaking sea and nearly capsized. In the following trough she recovered and, before the next wave broke, shot under the pier head into sheltered waters. As dawn broke she was quickly followed to safety by the Mary~PZ.16, and the Dart~80.PZ. The small crowd gathered at the pier head could now see a fourth lugger running for home – the Jane~26.PZ.

The Jane was a fine lugger barely 18 months old. Built at Penzance for John Thomas Wallis, of Mousehole, she had been completed just in time take part in the 1879 spring mackerel fishery. A brief note of her launch was published in the Cornishman of Thursday March 13th 1879:

On Saturday afternoon a first-class fishing-boat – the Jane – was successfully launched from Messrs. Mathews’ shipbuilding-yard. The Jane, the property of Capt, J. Wallis, of Mousehole, has a 46-feet keel and is the last of six boats for Mousehole which have been launched from this yard during the present season, all giving satisfaction, and their model and workmanship reflecting credit on Messrs. Mathews and their staff.

Cornishman of Thursday March 13th 1879

Although considered a first-class boat by local convention, the lugger Jane was only of 14-tons register, by measurement, and so was rated as a 2nd class fishing boat by the national rules and regulations then in force. Thus she was numbered – 26.PZ. Nevertheless, by build and form she was one of the highest class Mount’s Bay luggers.3

Her crew of seven had had a slight enough season in the North Sea, grossing a little over £60. On board that fateful morning were, Capt. John Thomas Wallis; second hand William John Williams (29); deck hands, Frederick Curtis (22), Nicholas Richards (22), William Tonkin (16), Peter John Harvey (16) and the boy, Philip Charles Worth (15). For their eight weeks or so away from home they stood to take home £3 15s each – and they were so nearly there.

About 6:55 a.m. as the Jane approached the spot where the Percy had been in trouble less than a quarter of an hour earlier, a breaking sea crashed onto her decks, but she rose through it. Momentarily the lugger was held in the surf’s crest, before sliding back into the following trough. As she did so a cross-sea, rebounding from the back of the pier, caught her bows throwing them towards the Mount. The following sea caught under her starboard quarter, carrying it shorewards till her bows pointed South East, and then rolled her over. In the process she may have struck bottom, as almost immediately the lugger broke her back and parted in two. The remorseless waves pounded the two halves together quickly reducing them to matchwood. For a while two heads could be seen in the wreckage, appearing and disappearing in the waves. But before any form of aid could be launched from the shore the two men disappeared for a last time. All that remained was a spreading mass of wooden wreckage being driven down the back of the Albert Pier towards the rocks under the railway station. Within 100 yards of safety the Jane had been lost with all hands.

Today, with our mass-media reporting international disasters of great magnitude and loss of life – almost as they happen – it is difficult to appreciate the impact of this disaster on a small fishing community. Mount’s Bay luggers were renowned for their sea-keeping abilities. Only a couple of years later the Duke of Edinburgh was to declare them the ‘finest craft afloat serving the daily fresh fish market.’ Renowned both for their speed and seaworthiness, no decked Mount’s Bay lugger had ever before foundered because of stress of weather. Indeed, the Jane was the first lugger to be lost with all hands in 40 years, since the un-decked Dolphin had foundered in May 1840.

The loss of the Jane struck the Mousehole community like a thunderbolt, and the aftermath of the tragedy dragged on for weeks. Wreckage was driven ashore along the back of the Albert Pier, and the beach at Chyandour. Within a week most of the wreckage of the boat and her equipment had been recovered. The hull was found in two mangled pieces. But there were no bodies found in the wreckage

Then, on the 15th day, the first of the bodies came ashore between Mousehole and Newlyn. It was the badly disfigured corpse of young Phillip Worth.

Four days later that of Frederick Curtis was washed ashore in nearly the same place. He could only be identified by his clothing.

Nicholas Richards’ body was found on Marazion beach the next day and was also identified by the clothing and a knife he carried.

A fortnight later, on November 12th, John Peter Harvey’s body was found on the eastern side of the Lizard.

The body of William Williams was not found until November 23rd. His corpse was recovered at Gunwalloe, and was only identified by the sea-boots he wore.

Perhaps it was this protracted recovery of bodies, as much as any other aspect that stamped this tragedy so indelibly in the minds of the local community. The bodies of Capt. Wallis and William Tonkin were never found.

The Mayor of Penzance set up a relief fund to provide for the widows and orphans of the Jane’s crew, as well as towards general damage repairs around the town – which was heavily hit by the storm. Part of the sum raised went to aid the recently formed Mount’s Bay Fishing Boats Mutual Insurance Club. This embryo insurance club had only been registered as a Friendly Society on March 8th 1880. It was largely the result on one man’s efforts – the Rev. W. S. Lach-Szyrma, the vicar of St. Peters, Newlyn. By no means all of the local boat owners were members of this club, but many were. At the time of the great storm of October 1880 some 80 to 100 boats were on the club’s books, but with only one year’s premiums having been paid, their current assets stood at £80. This October storm brought claims of £260 against the club, £200 of which was for the Jane.

When the Mayor’s relief fund was closed in January 1881, it stood at £1,754. Captain Wallis’s widow was awarded a capital sum from the fund, and Mrs Williams and the orphans were granted annuities of £13 and £6 10s. respectively. The award to Mrs Wallis and the purchase of the annuities accounted for £754. A total of £740 went towards general repairs to sea-front property and uninsured boat owners, and £260 was handed over to the Mount’s Bay Club.

Perhaps the most tangible memorial to the crew of the Jane was the new harbour at Newlyn, which commenced five years later. The loss of this lugger had brought home the paramount need for a safe, all tides, harbour for the fishing fleet, and the businessmen and burgesses of Penzance were at last aligned with the fishermen in this objective.

Although succeeding generations never forgot the loss of the Jane, the facts attending her loss gradually became obscured over the years; but there remained in Mousehole a constant reminder of the tragedy up until quite recently – Mrs Tamsin Williams.

Aunt Tammy, as she became known to many generations of Mousehole children, was William John Williams’ widow, and she lived until 1950 when she was 103. For 70 years she had been a widow, and throughout them she had received her annuity payment of 5 shillings a week.

Tony Pawlyn

March 2017

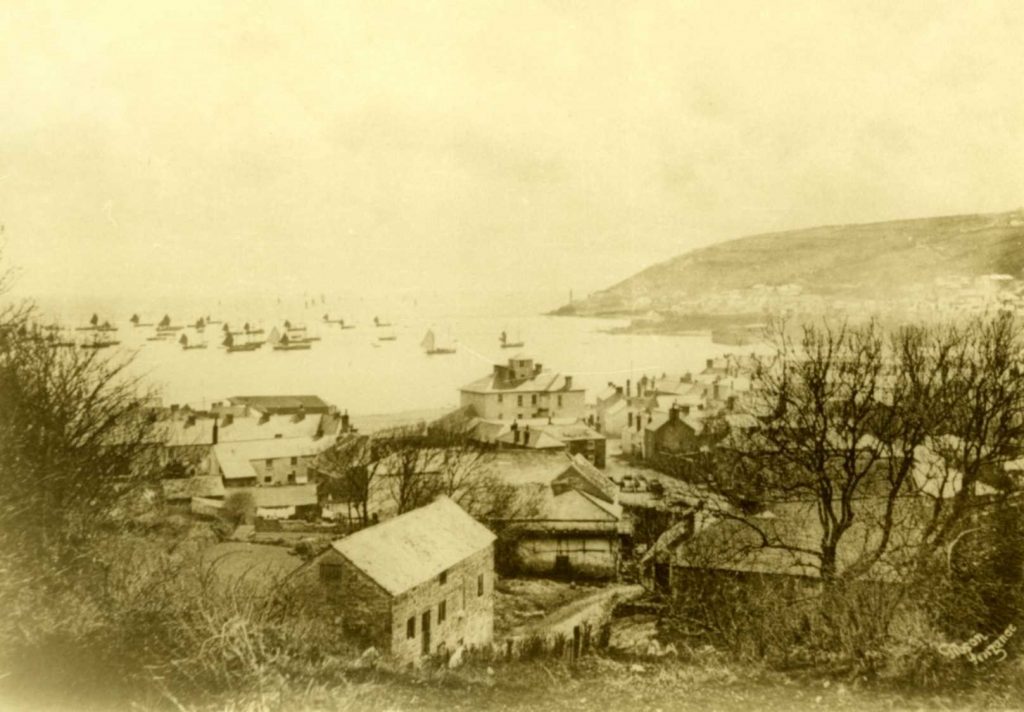

Note: The Gibson photos reproduced in this article were acquired by the author back in the 1970s, when he had Frank Gibson’s permission to use them gratis, so long as due acknowledgement was given as to their source. In 2017 the Gibson collection [sans wrecks], was purchased by the Penlee House Museum, Penzance.

- Mount’s Bay fishing boats were registered in the ‘Port’ of Penzance, and prior to 1869, they carried fishing numbers prefixed by the letter PE. – the first and last letters of the name of the port. However, the same letters applied to the port of Poole, and in 1869 the distinguishing letters for Penzance were changed to PZ.

- Abstracts from James Ladner’s pocket book, lent to the author by Owen Ladner in the 1970s

- Fishermen could be superstitious, and some regarded 26 as an unlucky number – being two 13’s