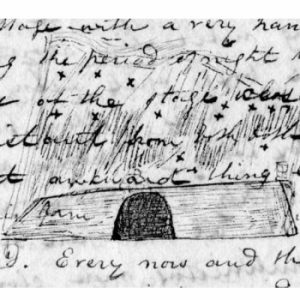

James’ sketch of the theatre at Buenos Ayres

Theatre of Buenos Ayres

It is often remarked that among men, they often fly from devotion to amusement, to unbend and as it were relieve the mind. So with me it is – from the church, whose solemn stillness – grandeur of size – and religious associations impress the soul with awe – I have gone to the Theatre, more to recover the mental elasticity & slightness, which saints & images had dispersed – nor without effect. The Theatre in external appearance would not be judged to be such. It is the last house at the end of a street and right opposite one of the churches. When the door is opened, you enter a small lobby at one end of which is a space railed in where you will find a person to issue out the tickets. We will suppose that you wish to go to the pit & you ask for a pit ticket. A great number of slips of paper are presented to you on which certain numbers are marked corresponding to the same number on the backs of the seats. Three dollars is demanded for each (21.d), & if you know the house you can select a seat in the part that will please you best.

Along with these pieces of paper marked Lunetas, you receive a slip of paper, which is alone to be delivered to the door-keepers, whilst your ticket will not be demanded of you before the intermission of the Comedy or Tragedy. The first night I visited the Theatre, the representations were to consist of a Tragedy, called ‘Ines de Castro’ & a farce called the Invisible Witness. According to my usual custom I arrived early, few persons were in the house, so that I had a better opportunity of scrutinising every place. In front of me was the stage with a very handsome drop scene, representing the period of night with stars. At the very edge of the stage close to the orchestra, & equidistant from the both stage doors is a most awkward thing like a Diogenes tub of this form [see illustration] where the prompter is stationed. Every now and then you perceive his head above his box, and if he is a vain man & proud of his elocution you will hear him distinctly drawling thro’ the play. Nothing is more calculated to annoy & to destroy the illusion to those within hearing. Immediately behind the prompter is the Orchestra which was very good indeed. Next came the pit, with its rows of benches, & each individual seat parted off from those on either side by two arms like an arm chair – numbered on the back & having a bottom cushion covered with crimson velvet. Altogether I was as comfortable in my birth in the pit as I could have been at home.

The other accommodations of the house con[sisted] of two tier of boxes and one gallery. I believe there is no difference between the dresses of the boxes both being dress circles. They appeared to be very so so, unpainted – with bare walls & prison like doors. Here are no benches but instead chairs of all patterns, ages & appearance – the persons who engage be box being obliged to provide chairs. This is a strange & most inconvenient fashion, for which I think no good reason can be assigned – & I hope will be done away with. Right in the centre of the lower circle is a large box for the governor & suite – nothing noticeable about it. The passage to the boxes & pit being the same, it is permitted here & often practices to go round the box lobby, or rather narrow passage, & very rudely & unceremonially obtrude your phiz in at the open doors for the purpose of scrutinising more closely the many lovely girls who fill the boxes. I have been astonished at the impertinence & coolness with which this is done, & could never bring myself to join in it, tho’ I believe I was a little over squeamish & gave the B. Ayrean ladies credit for feelings of delicacy & retiring modesty to which they have not the smallest claim of pretension. I could not help remarking the nonchalance with which they bore the most scrutiny of their personal charms, & that they in their turn investigated with a critical eye the persons of those who shewed themselves at the entrances of the boxes.

In the pit no ladies are permitted to be present. In the two dresses boxes the ladies and gentlemen sit together as with us – but in the upper circle of gallery females alone are to be seen, no male being allowed to enter therein. This is as it should be – then men being placed low in the scale of the ladies elevated to the rank of goddesses. To our eyes indeed this arrangement looks strange & unsocial – the protection of beauty – the shield of virtue – & the silence of scandal – & the preventive of those disgraceful scenes which shock the eye & ears of the virtuous female among us. Not even a father – husband – or brother can enter these sacred precincts of the Olympians – but are compelled to await them at the door when the entertainment is over, to conduct them home. One glance at the places occupied by the ladies would be one to induce a second. I had no idea that so many beauties could be collected together – non-expectation was in proportion agreeably disappointed. There was no great display of very elegant dresses – indeed there was rather an affectation of plainness, being mostly such as they would wear at home in the evening. Their heads were neatly arranged & every one wore the immense combs so common here. To be without a fan is a piece of forgetfulness of [which] they are never guilty – having them they are in constant employ. It was a very pretty sight to look along the phalanx of the goddesses & watch the evolution of hundreds of fans, now unfolded, now shut – now fluttered with great rapidity, now moved to & from with a gentle quiet at-my-ease motion.

Having now said so much about the interior arrangements of the Theatre and of the audience, you will probably expect me to say something of the dramatic department. I am sorry to say that my ignorance of the language incapacitated from deciding on this point. The music was very good. The declamation seemed to me unnatural & obstreperous. The characters, if not appropriately, were well & even richly dressed. I was soon tired of looking on & long ere the Tragedy was over wished myself elsewhere. I could not at all make out the plot, do what I could. At the most pathetic parts my eyes were dry & a smile at sometimes ridiculous contrast was on my lips. Judging of others by myself, I am persuaded either that the Tragedy or the Acting was very bad, because I did not observe but one lady, who was affected to tears – all the rest looking as comfortable & happy as on the most ordinary occasions. I think then this circumstance augured bad for the acting – I say for the acting – because I am most unwilling to charge the lovely natives with a dereliction from all true feminine feeling exhibited in a want of sympathy for the woes of others.

There was no great variety of scenery – rather a scarcity – and you were to fancy at one the scene before you to be the abode of this man & at another of that man perhaps his enemy.

The amusements of the evening always conclude with a piece in one act (they have no farces), at which I was a little more at home than in Tragedy. Indeed after the first night of my attendance, I never came to see the tragedy – but merely to have a laugh at the broad humour of the after-piece. Besides we used to have some person to unriddle to us what was unintelligible & by this means we could enjoy a hearty laugh. The points of wit depended on language – the double entendres – the coarsest jests were of course lost to us – but the comedy of action & pantomime being addressed to the eye & the feelings of nature called forth bursts of laughter. For instance we had the view of a house from one of the windows of which a young lady was looking out, apparently on the watch for some one. Shortly afterwards a jolly priest comes under the window and commences a conversation, the object of which we soon find to be to induce her to admit him into the house. She at first absolutely refuses – then hesitates & at last consents. A basket for the purpose is then let down from the roof, into which the priest with much demurring enters. He is gradually borne aloft in great trepidation – but instead of being allowed to get in at the window, he has the mortification to see it closed & to be left dangling in the air. Finding that his softest persuasions are ineffectual to soften his obdurate mistress, & becoming every instant more and more alarmed, his fear finally get the better of his prudence & he bawls lustily for assistance. By his outcries a parcel of boys are soon collected, who perceiving his ridiculous situation batter him with rotten eggs & other unpleasant missiles. In the midst of the hubbub arrives the Alcalde, at whose instance the poor fellow is lowered down & he is then taken into custody to answer for his misconduct.

I shall only mention one instance more where a stranger could enjoy a laugh. A country man came upon the stage with a jackass, loaded with wood, & carrying besides two fowls which he had bought for his wife. He was anxious to get his wood sold & to return home but he ha been for a long time unsuccessful. At last he received an offer for the whole from a barber which he accepted, meaning only to sell the wood for the price offered. As soon as he had agreed, the barber proceeded to remove the wood, & then took possession of the fowls – to the astonishment of the countryman who vehemently denied that these were included in the bargain & refused to part with them. The dispute grew high that the Alcalde was called in, & upon the testimony of two men, who chanced to hear the transaction, he decided that the fowls belonged to the barber. The poor payson was obliged to submit but swore revenge. Some days afterwards he entered the barbers shop in disguise & asked for how much he would undertake to shave him and his companero. The barber asked 8 reals (7.d) which was agreed to. The countryman being first operated upon, afterwards went out for his companero, & soon returned leading in the individual Jackass that had carried the wood, declaring that this was his only companion. The Shaver remonstrated in vain – his words were insisted upon & by the decision of the Magistrate who was summoned he was compelled to shave the Jackass. And oh it would have made even a cynic laugh to have witnesses the ludicrous repugnance and awkwardness on the part of the barber & the equal unwillingness and restiveness on the part of the Jackass during the operation. The fun of the thing was completely suited to the meridian of every capacity, gentle or simple, stranger or native, & accordingly was received with roars of laughter.

The performances at the Theatre are generally over at half past ten or eleven. The ceiling is very orderly and quite. No carriages are waiting at the door, but all trudge home on foot. The Theatre in general is open every alternate night – & even on those nights when certain performances are announced, should the weather prove rainy, the Theatre will be shut – most provoking to those whom rainy weather compels to look out abroad for amusement. In general the Theatre is well attended, particularly the pit & gallery – the price of the latter being so very trifling that it is within the compass of the lowest classes. Half an hour after the commencement you can get into the pit for 7.d but are not entitled to a seat.